|

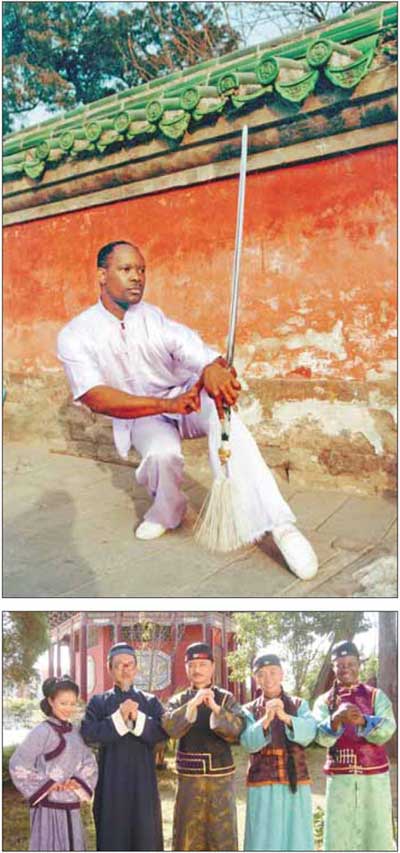

A young African boy came to China to look for the flying heroes he had seen in kung fu movies. He did not learn to fly, but other lessons had made him a hero in his own homeland, and an ambassador in China, where he has stayed for the last 30 years. He Na finds out the details. Children often have big dreams, to stand in the limelight in front of the cameras, the football field, or even in politics, but perhaps Luc Bendza had the grandest dream of them all. He wanted to fly. It was a special kind of flight he dreamt about - to be able to float through the air like all those heroes he saw in Chinese kung fu movies. While flight has proven impossible, the 43-year-old from Gabon's fascination with Chinese kung fu did lead him to great things. He has won several international martial arts awards, he speaks fluent Mandarin, and he has appeared in several movies and made numerous appearances on Chinese television. In addition to his acting, Bendza now works as a cultural consultant at the China-Africa International Cultural Exchange and Trade Promotion Association in Beijing. Kung fu movies were popular in Gabon in the 1980s and Bendza was a huge fan. "I really admired those people in the movies who could fly. They were able to fight for justice and help the poor. I wanted to be just like them, but when I told my mother I wanted to go to China and learn to fly she thought I was crazy," he recalls. Bendza began by studying Chinese with the help of Wang Yuquan, a translator working with a Chinese medical team in Gabon. Sometimes he skipped school to study with Wang, and also called him in the evenings to talk about China. "When my mother heard me speaking Chinese on the phone she was surprised," he says. "She even took me to see a psychiatrist. But I told her that I had made my decision no matter whether she agreed or not." Then Bendza opened a video rental store without telling his parents and saved $1,000 to help fund his move. "In the 1980s, $1,000 was really a lot of money. When I presented the money to my parents I could see the surprise on their faces," he says. "After they had confirmed the money wasn't stolen they both sighed with relief." But they were still not convinced. What finally swayed them was a phone call from Wang. "I begged Wang to make the call," says Bendza. "Wang told my parents how serious I was and asked them to give me a chance." Bendza's parents were both government officials and had hoped he would follow in their footsteps. However, they accepted his plans, while also betting with their son that he would soon return. It was 1983 when Bendza moved to China, at just 14 years old. There were no direct flights so he was forced to travel through several countries on a long arduous journey. "It was a really long and complicated journey for a child, but luckily I wasn't abducted by traffickers," he says. Bendza's uncle worked at the Gabon embassy in Beijing and picked him up at the airport. "He was puzzled that I kept looking left and right, my eyes searching for something," says Bendza. "I was looking for people who could fly." His uncle laughed when he said this and explained that it was movie technicians who made people fly. "I kept saying no and begged him to find the flying people for me. So he took me to Beijing Film Studio where I saw actors flying, hauled into the air on ropes," he says. He was disappointed and after just two months in Beijing, decided to go to Shaolin Temple in Henan. "There were few foreigners in China in the 1980s, especially black people from African countries. Wherever I went people pointed fingers at me like I was from another planet, but I wasn't annoyed because they were all very friendly," he says. "The people at Shaolin Temple were really amazing. Although they couldn't fly like in the movies, still their martial arts made a deep impression on me. I told myself I had gone to the right place." Bendza's Mandarin still wasn't good, so after less than a year he left the temple and returned to Beijing where he studied Mandarin at university for a year. After that he enrolled at the Beijing Sport University studying traditional Chinese martial arts. "I stayed at the university for more than 10 years and finished both bachelor and postgraduate studies," he says. "I really need to thank those teachers who not only taught me Chinese martial arts history and other subjects, but also helped me build a solid foundation for being a real martial artist." Bendza's natural aptitude for martial arts, and hard training saw him progress rapidly and won him recognition from many martial art masters. "The teacher would put a nail with the sharp end up under your bum when you were practicing a stance so if you lowered yourself too far the nail would hurt you," Bendza recalls. The tough training paid off though as Bendza won awards in China and abroad. He also attracted the eye of directors and he went on to play roles in both movies and television series. He did not tell his mother about these successes, and she only found out when she read about him winning an international martial arts competition in France. Bendza began to gain recognition for his achievements in Gabon, but the media there were initially unkind. One newspaper ran a front-page cartoon of him standing with two suitcases, a foot in China and a foot in Gabon, but with his head turned toward China. The insinuation was that he had turned his back on his homeland. "The media used the cartoon to show their dissatisfaction," he says. "When I returned to Gabon my mother told me I had to do something to change this bias against me. She took it very seriously." Bendza organized a free martial arts show as a way of changing opinions and media coverage become more positive. "When I left, my parents saw me off at the airport and told me they thought I was great. When they said that and my mother hugged me, I cried like a baby. That was the first time in 10 years I had won recognition from my mother," he says. Martial arts changed his life and he has hopes to promote it across Africa. But his work has also moved away from purely performing toward promoting cultural exchanges. As a member of International Martial Arts Association, he organizes Chinese martial arts teams to perform and teach in Africa. Bendza has been in China for 30 years and witnessed the country's reform and opening up process. He married his Chinese wife in 2007 and they have a 16-month-old son. "I have become used to life in China and enjoy being here with my family very much," he says. By He Na ( China Daily) |

孩提時(shí)代總會有很多宏偉的夢想,或是成為眾人矚目的明星球星,或是在政壇大顯身手。Luc Bendza (呂克?本扎)的夢想或許是其中最遠(yuǎn)大的,他想要飛檐走壁。 他渴盼的是一種奇特的飛翔體驗(yàn)—可以像中國功夫電影中的英雄那樣,在空中來去自如。 盡管飛翔之夢最終擱淺,這位43歲的加蓬人對中國功夫的癡迷確使他收獲頗豐。他多次于國際武術(shù)比賽獲獎,普通話流利,曾參演過多部影視劇。 隨著時(shí)間的流逝,本扎有了更大的愿望那就是把中國武術(shù)和文化推廣到非洲。演戲作為興趣愛好,如今的本扎在北京的中非國際文化交流與貿(mào)易發(fā)展協(xié)會擔(dān)任文化顧問專門致力于中非文化交流。 功夫電影于上世紀(jì)八十年代在加蓬風(fēng)靡,呂克就在當(dāng)時(shí)成為了一名超級粉絲。 “我真的很崇拜電影里那些行走如飛的高手。他們可以為正義而戰(zhàn),幫助弱小。我想成為像他們一樣的人,可是當(dāng)我的母親得知我要去中國學(xué)習(xí)輕功的時(shí)候,她認(rèn)為我失去理智了。,”他回憶到。 呂克在王玉泉的幫助下開始學(xué)習(xí)中文,王玉泉當(dāng)時(shí)在加蓬的一個(gè)中國醫(yī)療隊(duì)擔(dān)任翻譯。有時(shí)他會翹課找王玉泉學(xué)習(xí)中文,有時(shí)也會在晚上打電話給王玉泉談?wù)撚嘘P(guān)中國的情況。 “我母親聽到我在用中文打電話時(shí)感到很驚訝,”他說到。 “她甚至帶我去看過心理醫(yī)生。但是我告訴她無論她同意與否,我決心已定。” 呂克還是很有生意頭腦的,他之前就瞞著父母私底下開了一家小的錄像帶租賃店,攢了1000美元,誰都沒有告訴。 “在上世紀(jì)八十年代,1000美元可真是一筆不小的數(shù)字了。當(dāng)我把錢放在父母面前時(shí),他們簡直難以置信。”他說,“確認(rèn)過這筆錢并非來路不明之后,他們大大松了口氣。” 但我并未完全說服他們,后來是王玉泉的一個(gè)電話使他們開始動搖。 “我央求王老師打電話給他們,”,B呂克說,“王告訴我父母我是十分認(rèn)真的,希望他們能給我一個(gè)機(jī)會。” 呂克的父母都是政府官員,因此也希望他能子承父業(yè)。然而,他們最終還是妥協(xié)了,雖然他們打賭兒子很快就會回國。 1983年,年紀(jì)14歲的呂克來到了中國。由于當(dāng)時(shí)沒有直航,他不得不輾轉(zhuǎn)多地,一路旅途勞頓。 “對一個(gè)孩子來說,的確是一段漫長顛沛的旅程,所幸我沒有被人販子拐賣掉。,”他說。 “我舅舅當(dāng)時(shí)在在加蓬駐華大使館工作,他去機(jī)場接我時(shí)發(fā)現(xiàn)這孩子好像有點(diǎn)不正常,因?yàn)樗幻靼孜覟槭裁床煌5臇|張西望,好像四處搜尋著什么,”呂克說,“我在找會飛的人。” 他舅舅聽到后大笑,并解釋說那是電影特效。 “我不停否認(rèn)并且央求他幫我找到會輕功的高手。舅舅無奈就帶我去了北京電影制片廠,那里的演員被繩子吊在空中飛行。”他說。 他十分失望,在北京待了兩個(gè)月之后,決定去河南少林寺學(xué)藝。 “上世紀(jì)八十年代的中國幾乎沒有外國人,更別提非洲的黑人了。無論我走到哪,人們都會指指點(diǎn)點(diǎn),好像我是外星人一樣,但我并不生氣,因?yàn)樗麄兌挤浅S押谩!彼f。 “少林寺的高手們個(gè)個(gè)功夫了得。盡管他們也不能像電影里那樣施展輕功,他們的武術(shù)絕技仍讓我大開眼界。我暗嘆自己真是來對了地方。” 呂克的普通話當(dāng)時(shí)還不是很流利,在少林寺待了小一年后他又回到北京,在大學(xué)里學(xué)習(xí)了一年中文。 之后,他在北京體育大學(xué)學(xué)習(xí)中國傳統(tǒng)武術(shù)。 “我在體大待了十多年,拿到了我的學(xué)士和碩士學(xué)位。,”他說。 “我真的很感謝學(xué)校的老師們,他們不僅教授我中國武術(shù)歷史和其他科目,同時(shí)也幫我奠定了成為一名真正武師的堅(jiān)實(shí)基礎(chǔ)。” “在武術(shù)上的天賦以及刻苦努力的練習(xí)使得呂克進(jìn)步飛速,并且贏得了眾多武術(shù)大師的認(rèn)可。 “練功時(shí)老師會把釘子的尖頭朝上放在你的臀部下方,一旦你偷懶身體下沉,就會被戳到,“”呂克 回憶到。 艱苦的訓(xùn)練終于有所回報(bào),呂克在中國和國際賽事上均有所斬獲。 他也因此得到了導(dǎo)演的關(guān)注,參演了一些影視劇。 他從未主動將自己的成功與母親分享,直到他母親在新聞中得知他在法國獲得國際武術(shù)比賽的冠軍時(shí)才了解到兒子的輝煌。 呂克的成就在加蓬也開始逐漸得到認(rèn)可,但媒體最初對他并不友好。一家報(bào)紙?jiān)陬^條刊登了一副漫畫,漫畫里呂克手提兩個(gè)行李箱,一腳踏在中國,一腳踏在加蓬,可頭卻扭向中國。暗諷他背棄了自己的祖國。 “媒體通過漫畫來表達(dá)他們的不滿”,他說,“回到加蓬后,我母親說我需要做些什么讓他們改變對我的偏見。她十分在意這一點(diǎn)。” 于是呂克組織了一場免費(fèi)的武術(shù)表演以此來改變輿論,媒體報(bào)道也隨之變得更積極正面了。 “要離開時(shí),父母去機(jī)場為我送行,他們覺得我真的很棒。說到此刻我母親緊緊擁抱著我,我涕淚橫流。那是十年來我第一次得到母親的認(rèn)可。,”他說。 武術(shù)改變了他的人生,他同時(shí)也希望將其在非洲發(fā)揚(yáng)光大。而他的工作并非僅僅局限于文化交流層面的促進(jìn)。 呂克 在中國生活了長達(dá)三十年之久,同時(shí)也見證了中國改革開放的歷史進(jìn)程。2007年,他娶了一位中國妻子,如今他們的兒子已經(jīng)14個(gè)月大了。 “我在中國早已入鄉(xiāng)隨俗,跟我的家人在這里生活的十分愉快。,”他說。 相關(guān)閱讀 (中國日報(bào)記者:何娜 編譯:實(shí)習(xí)生詹千慧) |