Spider bite offers a lesson

Updated: 2013-09-29 07:26

(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

I lay with my teeth clenched and my hands gripping the sides of a hospital bed. Strangers in white coats filled the tiny room. Waves of pain lapped from my abdomen into my chest as the venom worked its way toward my heart.

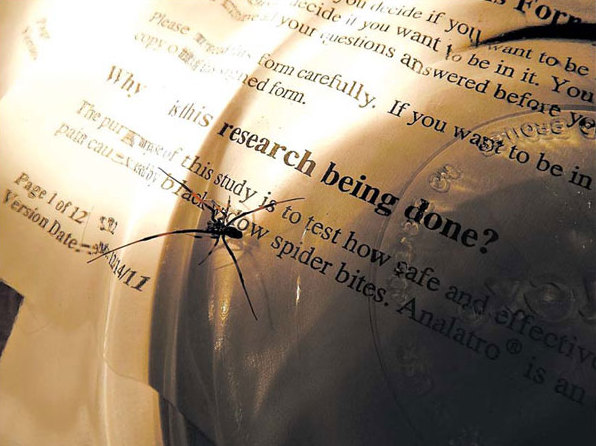

An experimental antivenin drug was about to be injected into my bloodstream.

As a professional outdoorsman, I have been lucky with snakes and reckless with bears. I have had some close calls with lionfish. It figures that the thing to finally put me down would be living on my own front porch.

The black widow's graceful form and red hourglass marking have made it America's most recognizable spider. Black widows are surprisingly shy and retiring. People in the United States probably walk past hundreds of them in a lifetime without even realizing it.

|

Black widow spiders are common, but they shy away from people. A male black widow, found in Virginia. Jackson Landers |

Each one packs enough venom to lay out a heavyweight boxer for days. Both sexes carry the same venom, but the females have more of it and their fangs can inject it deeper.

Still, globally only a few people each year are killed by widow bites.

The perimeter of my house in Virginia turned out to harbor a village of black widows. Interested in learning about them, I sometimes captured a dozen in a day.

One spring afternoon, I decided to go fishing. On the porch where I had removed so many black widows, I kept a pair of water shoes and some fishing tackle. I put them in my car and drove to my favored spot.

I donned the shoes. Within about a dozen steps, I felt a stinging sensation, and realized what must have happened: a black widow from the porch had made its home in my shoe.

Some people are more affected by the venom than others. Most healthy adults experience a lot of pain and recover on their own. But others become incapacitated, and some die. Which group would I fall into? Why make a big deal out of nothing?

I decided to wait and find out before driving. I dipped my foot into the cool water and decided to pass the time by fishing.

Three catfish later, the symptoms were progressing. I felt a warmth in my abdomen. This turned into pressure, then cramping. I headed for the University of Virginia hospital, in Charlottesville.

My research had taught me that while an antivenin exists, few patients actually get it.

The medicine has changed little since 1895, when it was discovered by a French physician, Albert Calmette. By injecting spider or snake venom into a horse, Calmette induced symptoms of a bite, causing the body to produce antivenin. Blood could be drawn from the horse, and the substance could be isolated and stored for later use.

While the antivenin has saved many lives, it carries dangers of its own. Some patients have a life-threatening allergy to horse proteins. So the medicine is given only if the victim seems to be near death; most patients are expected to tough it out, an ordeal that can take days.

That night, residents and medical students stopped in to gawk; few had ever seen a black widow patient.

Dr. Christopher Holstege, a calm toxicologist, said he wanted me to be part of a test of a new form of antivenin. The drug, Analatro, was made in sheep, and it had fewer impurities to which the body could react. It sounded promising, but I could not take pain medications that would mask the drug's effects. And the side effects were not well understood. Still, I could not bear not to volunteer.

My biceps cramped. I shivered and twitched. At midnight, the crowd was silent as the substance was injected. A wonderful warm flow spread from my arm into my chest, then my abdomen.

It could take years of study before Analatro is ready, but it could completely change the way black widow bites are treated. Instead of making patients wait through days of pain to avoid an allergic reaction, doctors could administer antivenin immediately and discharge them within hours.

When I got home at 4 a.m., I collapsed into bed. The next afternoon, I hopped to the kitchen to make coffee. There on the floor, I spied a little brown spider. I dropped a jar over it and captured an excellent specimen of a male black widow. I took a series of photographs, and then it met its end.

The New York Times

(China Daily 09/29/2013 page11)