A playful reconstruction

Updated: 2013-07-07 08:32

(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

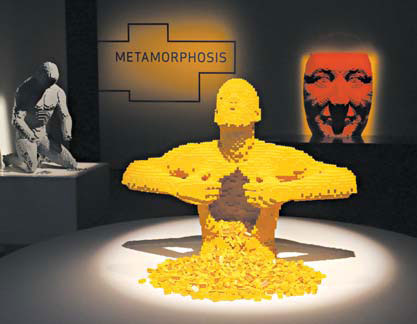

The works in the "Meta-morphosis" gallery and "Swimmer," above, use only colors ordinarily available in Lego sets. Photographs by Suzanne DeChillo / The New York Times |

It is best not to look too closely at Edvard Munch's screamer at the exhibition "The Art of the Brick" at Discovery Times Square in New York. Because then you would see that the head is pieced together out of beige and white Lego blocks, their studs protruding.

Leonardo's "Mona Lisa," on display nearby, has a smoother surface, composed of 4,573 "bricks," but you'd never mistake it for the original.

The portrait's creator, Nathan Sawaya, seems perfectly content with that. He has snapped together a Legoistic survey of art masterpieces, along with galleries of original constructions. In varied forms, this show of his work has appeared in other cities and toured internationally.

Everything is built from Lego blocks using only the colors that the Danish company makes available. And mostly, it looks it. Mr. Sawaya proudly notes on the "Mona Lisa" label that "a blurred photo of the brick replica version could easily be mistaken for a blurred photo of the original."

Such a mistake is less likely with Vermeer's "Girl With a Pearl Earring" (1,694 pieces) - the painting's ornament consists of a transparent Lego sphere - and seems impossible with the table-size version of the Great Sphinx of Giza (2,604 pieces). But the resemblance to blurred photos is useful to keep in mind when confronted with an exhibition composed of Lego pieces.

In fact, it is difficult to walk through this exhibition and pass a version of Rodin's "Thinker" (4,332 pieces) or see Mr. Sawaya's own life-size piece "Blue Guy Sitting" (21,054 pieces), and not admire the ambition and skill. In "The Thinker" the pieces weave a knot of relations among the face, bent arm and closed fist. In "Blue Guy Sitting," we see that blocks have molded an embodiment of relaxed contentment.

Some constructions are alluring for other reasons. The dinosaur (80,020 pieces) impresses with its scale, occupying an entire gallery, its snapped-together plastic pieces resembling fractured fragments of fossilized bone. And the Moai figure from Easter Island (75,450 pieces) is large enough so that you almost don't have to blur its pixelated construction mentally to imagine the original's sculptured curves.

Not everything works. Mr. Sawaya's

version of Caspar David Friedrich's "Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog" (3,002 pieces) hardly retains, as the label suggests, "the same feeling of awe in the vastness of the scene." Some of Mr. Sawaya's original works and commentary also have a greeting card simplicity. ("Dreams are built," reads a homily on one wall, "one brick at a time.")

But despite some awkward examples, we get a very particular kind of pleasure from these constructions. It has something to do not just with the use of toy blocks as an artistic medium but also with the character of the bricks themselves.

Mr. Sawaya's playfulness is contagious. And the limitations are part of the appeal. Basic Lego bricks are so minimalist, almost anything made using them inspires a bit of wonder.

Mr. Sawaya's use of rectangular blocks ensures that we can't take even the smoothness of a line for granted. So we see how continuous curves are created out of discrete elements.

His constructions almost reflect an early digital aesthetic, which is why these Lego constructions can seem as pixelated as a dissolving digital photo. Mr. Sawaya offers a playful approximation of reality while celebrating Lego's lure.

The New York Times

(China Daily 07/07/2013 page9)