Detours on road to clean fuel

Updated: 2013-06-30 07:36

By Diane Cardwell(The New York Times)

|

|||||||||

|

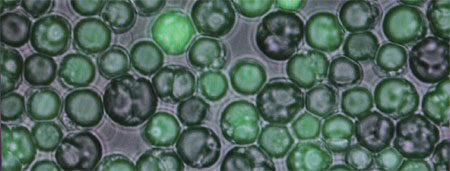

Solazyme extracts oil from algae grown in tanks, though it has been used not as a fuel but as a moisturizing agent for aging skin. The algae's brighter green cells contain more oil. Jim Wilson / The New York Times |

Jonathan S. Wolfson and Harrison F. Dillon started out in mythical Silicon Valley fashion. A decade ago, the two college friends began working in Mr. Dillon's garage, growing algae in test tubes in a quest to use biotechnology to create renewable energy. Then they found a small group of investors.

Now, they have released their very first algae-derived oil produced at a commercial scale: pale, odorless and dispensed from a small matte-gold bottle with an eyedropper, not for fuel tanks but for the faces of women worried about their aging skin. It sells for $79 a 30-milliliter bottle and may be just the thing that lets their company, Solazyme, coast past the point where so many other clean-tech companies have run out of gas: the shift to commercial-scale production.

The hope is that Solazyme will stay afloat by making oils that can serve a variety of functions - like moisturizing skin or replacing butter and eggs in the baking process. The next step is making huge quantities of renewable energy products at a price that can compete with fossil fuels.

For years, policy makers, environmentalists and entrepreneurs have trumpeted the promise of harnessing the power of the sun, wind, waves, municipal solid waste or, now, algae. Since 2007, United States energy consumption from renewable sources has grown nearly 35 percent, and now accounts for about 9 percent of the total, according to the Energy Information Administration.

But there have been prominent failures. Once-promising clean-tech ventures that attracted hundreds of millions in support from the United States government - like the solar panel maker Solyndra, the cellulosic ethanol maker Range Fuels and the battery supplier A123 Systems - have failed. The next generation of biofuels, based on nonfood plants, is still struggling to take off.

Venture capital has slowed, and new energy businesses burn through large amounts of capital over many years for research and early-stage equipment before demonstrating their promise. Worldwide in 2012, venture capital investing in clean technologies fell by almost one-fourth, to $7.4 billion, from $9.61 billion in 2011, according to the Cleantech Group's i3 Platform, a database.

So clean-energy companies can't rely only on the classic approach in which investors get a fat, fast return. They need a combination of government grants, industrial partnerships and a willingness to pursue higher-value product lines en route to larger, but lower-margin markets.

"The problem with a lot of clean-tech deals is that they have been about the way you make things in high volume or in production, which means you can't prove out the ideas unless you build factories and actually make things in volume," said Andrew S. Rappaport, a board member of Alta Devices, a solar film start-up.

Solazyme's story shows just how circuitous the road to profitable energy technologies can be.

When they first began, Mr. Dillon and Mr. Wolfson considered focusing on using algae to produce hydrogen, but hydrogen-powered vehicles never took off.

The Solazyme partners realized they needed to make a product that could use existing equipment and infrastructure, and fuel oil seemed the best bet. The problem with producing it is that volume is king. It didn't matter if Solazyme made a terrific product - if it couldn't make enough, the business would never succeed.

Cellulosic fuel may soon achieve real scale: the United States Energy Department predicts that there will be 303 million liters in commercial production by 2015. But companies using algae will take until 2022, officials predict.

At Solazyme, the partners stepped up testing early, trying to make something that mimicked existing fuel oil. They also re-engineered the microorganisms to see what else could come out.

"The point was still a straight line to fuels, but it started to be clear how long this was going to take," Mr. Wolfson said of the company's evolution toward developing multiple product lines.

The big discovery was that algae could make oils that, biochemically, looked a lot like others found in nature or already in use in the marketplace. But the partners had sold investors on an energy business, not one that made cosmetics, nutritional supplements and soap. They had also told their board that they would be able to make fuel through photosynthesis, but growing algae where they could get enough sunlight required huge ponds of water and the risk of plant loss.

After scrambling to come up with an alternative, Mr. Wolfson and Mr. Dillon told their board they would grow algae in tanks to make the specialty oils for ancillary markets, using the proceeds from those sales to support the fuel business while it developed.

Their main backers, who had already invested roughly a combined $1.3 million, agreed to finance further testing of the idea.

Several board members eventually left, and several venture capitalists who had been interested in leading rounds of financing withdrew because the founders insisted on pursuing multiple markets, Mr. Wolfson said.

"It's very true that if you try to do too many things and you don't focus as a company, you'll fail - focus actually does matter," he said. "That's portfolio theory for them. 'I'm making a bet on you on fuel; I want you to focus on that.' What they didn't really understand is our platform is a focused platform to produce oils."

The team engineers the microbes to produce oils with different properties. One might be a fat with the mouth feel of cocoa butter in chocolate, or something that mimics palm kernel oil to go into soap. Starting with a one-milliliter vial, technicians multiply the algae in a broth rich in sugar and other nutrients, moving them into progressively larger vats until they reach anywhere from 5 to 600,000 liters.

The scientists deprive the algae of nitrogen, putting them under stress that causes them to produce oil. The oil swells their cells, up to 85 percent of their mass.

Tanks, rollers and other equipment squeeze the oil out of the liquid. No matter what kind of oil, the process varies little, said Peter J. Licari, Solazyme's chief technology officer, and is easily adapted to make the complex sugars that went into the original Algenist skin care line.

The company has a multiyear agreement with Mitsui, the Japanese conglomerate, to tailor oils for chemical and industrial markets. In a joint venture with Solazyme, the Brazilian agricultural and food giant Bunge is building a plant next to its sugar cane refinery in south central Brazil; it will use the sugar to feed the algae, which it expects to make up to 114 million liters a year of oil for soaps and other products.

"The higher returns we can show out of each plant to start out with, the faster we can get plants financed and built," Mr. Wolfson said. The company expects to charge 60 percent more for the cosmetic oils than they cost to make, compared with 30 percent for fuels and chemicals, and 40 percent for nutritional products.

One attempt at branching out fell apart on June 24, when Solazyme dissolved a joint venture with Roquette Freres, a starch processor. The companies had been using algae to make low-saturated fats and oils without transfats, as well as a powdered supplement, Almagine, meant to replace eggs and saturated fats. But the companies said they could not agree on a marketing strategy.

Analysts say the company's operating figures suggest there is still more promise than delivery.

Last year, Solazyme had a net loss of $83 million on $44 million in sales. It took on roughly $185 million in debt earlier this year. Even so, analysts are optimistic about the company's prospects, despite some who express skepticism that Solazyme will ever develop the fuels.

"Fuels is still an opportunity for them," said Rob Stone, a research analyst who tracks clean tech. But he added that because the new, commercial-scale manufacturing capacity could be used entirely to satisfy demand in the higher-value markets, it might not make sense for Solazyme to use up its production space to make lower-margin fuels: "I think they could make a very large company without ever doing much at all in the fuel business."

The New York Times

(China Daily 06/30/2013 page9)