Myths and mountains

Updated: 2013-02-17 08:41

By Edward Wong(China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

A closer view of Lo Manthang, the walled capital of Mustang, where visitors should proceed slowly and explore some of the hidden corners. |

|

Trekkers' camps dotted the high grasslands. |

|

Farmers out in the fields cut down golden stalks of barley during the harvest in the villages. |

The southern brae of the Himalayas in Nepal offers trekkers landscapes and glimpses of faith that resonate across time, Edward Wong discovers.

Mustang was a caldron of myth, as I discovered on a 16-day trek in September. Modernity was creeping in to the area, but the stories that people told had evolved little over centuries. As I walked through the valleys and white-walled villages, I heard tales that brought alive the harsh land, a place of deep ravines and stinging winds and ancient cave homes. I had longed to visit Mustang ever since I got a glimpse of it while trekking the nearby Annapurna Circuit 12 years ago.

On the northern arc of the circuit is the village of Kagbeni, with its red-walled monastery. To the north is an expansive gorge carved by the Kali Gandaki River in Nepal.

Beyond lies Upper Mustang, or the Kingdom of Lo, forbidden to those who did not have a permit from the Nepalese government.

As a boy, I had seen my mother embrace certain Buddhist beliefs, and later I began walking paths in the Himalayas in search of something transcendent in the landscape and the abiding expressions of faith.

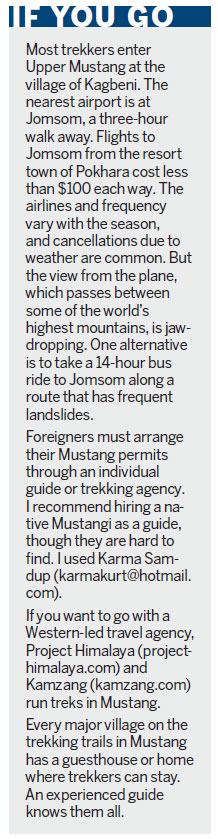

Last year, nearly 3,000 tourists entered Upper Mustang, according to statistics at a government office in Kagbeni, an increase of more than 25 percent from about three years earlier.

The permit fee for entering Upper Mustang - $500 for 10 days, and $10 for each additional day - deters many travelers. The low numbers, though, are welcomed by those trekkers looking to avoid the busy trails.

After a week in the Katmandu Valley, we flew north. Many trekkers rush from Kagbeni to Lo Manthang, the walled capital of Mustang, and back in 10 days. We decided to go more slowly and explore some of the hidden corners along the way.

Summertime in Nepal is when some of its last remaining nomads set up camp in the high grasslands west of Lo Manthang.

In that area, too, are peaks of more than 6,100 meters beckoning to be explored.

The eastern half of Mustang is more remote, and it has some of the best-preserved Tibetan Buddhist cave art in the world.

Each day of the trek, I marveled at how the landscape of Mustang was unlike anything I had seen in the Himalayas.

It was a place of canyon vistas revolving around the enormous valley of the Kali Gandaki.

The trekking routes on both sides of the river ran up and down side valleys. The rivers were low most of the year, but some summer monsoon rains meant we had to ford rivers a half-dozen times.

Much of Upper Mustang is a desolate place, inhabited by about 5,400 people and once crossed only by Tibetan pilgrims and yak caravans.

We entered the area on the second day of the trek. There, at a wide stretch of the Kali Gandaki, the waters were flowing high and fast. All our gear was lashed to three horses. Besides the guide Karma, our team consisted of Gombo, a horseman from Lo Manthang, and Fhinju, an ethnic Sherpa cook.

After the trail crossed the Kali Gandaki, it climbed steeply up to the village of Samar, considered the wettest and greenest place in Mustang.

Right before dusk, we crossed a pass draped with Tibetan prayer flags and walked down to a lodge.

Exhausted from a long day of trekking, my friend and I sat down in the warm kitchen for dinner. For dessert, there was apple pie with custard.

From next door came the sound of a pounding drum. "Traveling lamas," Karma said.

Over the next days, we settled into our trekking routine: Get up at 6 or 7 am, eat breakfast, walk for six to eight hours, reach a village before nightfall.

The countryside became more barren the farther north we went. The hues of the mountains - shades of red and brown and ocher - changed each day, and varied with the movement of the sun.

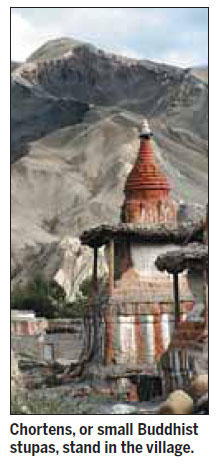

All across the rugged land, people had built Buddhist chortens, or small stupas, atop hills, on pathways leading into villages and even inside caves, in part to ward off spirits that would do them harm. Tibetan Buddhism and the myths were intertwined threads that were in turn woven into the landscape.

With the tail end of the monsoon came the harvest. Villagers were out in the fields cutting down golden stalks of barley.

We reached Lo Manthang after that climb and a couple of nights camping near nomad families. We sat in their black yak-wool tents and sipped cups of buttermilk tea.

Later, the gargantuan Thubchen Monastery beckoned. Its towering roof was held up by a forest of wood pillars, and its enormous gilded statues inspired awe.

After two days, we left, following Karma to a place just as singular but hidden by the land. We approached a cave east of the Kali Gandaki gorge that was reachable only by a vertical climb. We took off our packs and scrambled up using our hands. One slip and we would have plummeted hundreds of feet to the valley floor.

This was Tashi Kabum, a cave temple that local villagers had opened to the public only a few years ago. Inside was a large white chorten, and painted on the cave walls and roof are some of the best preserved ancient Buddhist art I had ever seen.

I could make out lotus petals on the roof. On one wall was a portrait of a lama in red robes. More enigmatic was a painting of a smiling, ivory-skinned man in a seated position. His face was illuminated by sunlight streaming through an opening in the cliffside.

Fhinju, our Sherpa companion, brushed his fingers over the painting. "Chenrezig," he said, and bowed his head in prayer.

For Tibetan Buddhists, Chenrezig was a Bodhisattva embodying compassion. Growing up in a US suburb, I had watched my mother pray nightly in our living room to a statue of the Chinese incarnation, Guanyin.

Here, as far from my childhood home as it was possible to be, he gazed out at me again. Faith in him had crossed borders and transcended time.

The New York Times Syndicate

(China Daily 02/17/2013 page16)