Farewell to the city's precious stone

Updated: 2013-01-06 11:58

By Elizabeth A. Harris(

The New York Times

)

|

|||||||||

|

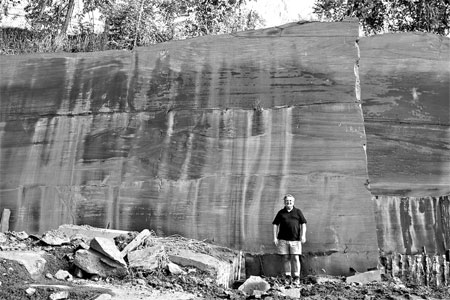

Mike Meehan, above, closed Portland Brownstone Quarries, sending stone fabricators scrambling for the material seen throughout New York. Christopher Capozziello for The New York Times Brian Harkin for The New York Times |

Brownstones occupy a unique place in the New York City psyche, as one of the city's most prototypical signposts, like yellow cabs and fast walkers.

Thousands of these structures are crammed into the five boroughs. Most of them are not only cast from the same mold, but were also made from the same stone, a brown sandstone quarried in Portland, Connecticut.

After being mined on and off for centuries, the Portland Brownstone Quarries, the very last of a kind, closed down this fall.

Preservationists are bemoaning the chance for a perfect match for the city's ubiquitous stone. And as Portland's diamond-studded saws slowed to their final rest, some stone fabricators began to - lovingly, respectfully - hoard the stuff.

"We're all scrambling to grab that stone," said George Heckel of Pasvalco, stone fabricators in New Jersey. "If you're thinking about achieving the look and feel of a New York City brownstone, you're not going to get that anymore."

Not everyone, however, is sad to say goodbye to this particular building block.

"I remember some quote saying it was the worst stone ever quarried," said Timothy Lynch, the executive director of the Buildings Department's forensic unit. "It's like New York City is covered in cold chocolate."

That old-time brownstone hater was likely to be Edith Wharton, who called it the "most hideous" stone ever quarried.

Today, architectural conservators and historians say that most of the city's "brownstone" facades have been replaced with brown cement-based masonry.

Brownstone began appearing in a significant way during the first half of the 19th century, and it quickly became the stone of choice for row house developers. (Brownstones are actually brick houses built with a stone facing.) Stone from Portland's quarries came out of the ground near the Connecticut River, so it was easy to get it to cities up and down the East Coast - and it was relatively soft, which made it easy to carve. Unfortunately that softness, along with money-saving methods used by developers and the extremes of the city's weather, made the stone liable to crumble, crack and flake.

"By the late 19th century, people were already complaining about this," said Andrew S. Dolkart, director of the historic preservation program at Columbia University.

The stone fell out of fashion, and by the 1940s, the Portland quarries, flooded by the Connecticut River in a major storm, were shuttered. It wasn't until the mid-1990s that Mike Meehan, a geologist with a background in coal exploration, reopened the ground at the edge of the quarry, slicing chunks of brownstone off a wall about 6 meters high and 200 meters long.

But most of the area is still filled with water, and Mr. Meehan's closest neighbor is a recreational water park, where zip lines crisscross an old brownstone quarry.

"We're up here breaking stones and there are people over there yelling, 'Yay!' " Mr. Meehan said. "It's a pleasant diversion at lunchtime."

Brownstone, which is really just a brown sandstone, is still quarried in a few spots around the world - including Britain, China and Utah - but experts say there is nothing quite like the stone from Portland. Much of Mr. Meehan's stone has been used in historic buildings and restoration projects, including Cooper Union, as well as lavish private homes.

"I'm telling you, he was our hero," said Michael Devonshire, an architectural conservator and materials expert at Jan Hird Pokorny Associates, a New York architecture firm that specializes in preservation.

Mr. Meehan said his company had extracted what it could from the quarry without making significant investments to get more. At 63, he said, he is ready to move on.

But he is among those hoarding some of the remaining little slabs.

"I'm going to keep working the stuff for my retirement," he said. "Bird baths, benches, things like that."

He just wants to carve away with his circular saw for fun. If his neighbors get upset about the noise, he added: "I'll make each one of them a bird bath. And then how could they complain?"

The New York Times

(China Daily 01/06/2013 page10)