Already squeezed, Australia's koalas are facing a killer disease

Updated: 2012-03-04 07:49

By Karen Barrow(The New York Times)

|

|||||||||

|

A bacterial infection joins climate change and habitat loss as a threat to koalas. A Sydney wildlife park. Torsten Blackwood / Agence France-Presse - Getty Images |

The koala, one of Australia's most treasured creatures, is in trouble.

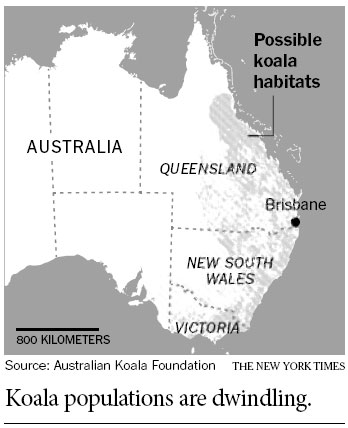

In Queensland, the vast state in Australia's northeastern corner, surveys suggest that from 2001 to 2008, their numbers dropped as much as 45 percent in urban areas and 15 percent in bushland.

While climate change and habitat loss are affecting koalas and many other Australian animals - from birds and frogs to marsupials like wombats, wallabies and bandicoots - it is a bacterial infection that is worrying many scientists about the fate of the koala.

"Disease is a somewhat silent killer and has the very real potential to finish koala populations in Queensland," said Dr. Amber Gillett, a veterinarian at the Australia Zoo Wildlife Hospital in Beerwah.

The killer is chlamydia, a class of bacteria far better known for causing venereal disease in humans. Recent surveys show that chlamydia has caused symptoms in up to 50 percent of Queensland's wild koalas, with more probably infected but not showing symptoms.

The bacteria - transmitted during birth, through mating and possibly through fighting - come in two strains, neither the same as the human form. One form can jump to other species, but so far there is no evidence that it has spread from koalas to humans or vice versa.

Chlamydia causes a host of symptoms, including eye infections that can lead to blindness, respiratory infections and cysts.

The epidemic has been severe in Queensland, where most koalas are infected with koala retrovirus, said Dr. Gillett. This retrovirus is an H.I.V.-like infection that suppresses the immune system and interferes with its ability to fight off chlamydia.

Treating chlamydia in wild koalas is a challenge, Dr. Gillett said. Only a small percentage of the animals can be treated successfully and returned to the wild. And infected females often become infertile, so future population growth is affected as well.

There is no treatment available for koala retrovirus, but researchers are working to test a vaccine that would help prevent further spreading of chlamydia.

A study published in 2010 in The American Journal of Reproductive Immunology found that this vaccine is safe and effective in healthy female koalas. Further work is being done to test it in koalas that are already infected.

Peter Timms, a professor at the Queensland University of Technology who is leading the effort to test the chlamydia vaccine, is hopeful that there will be another trial this year to test it in captive male koalas, followed by wild koalas. If all goes well, plans can be set in motion to distribute the vaccine.

One possibility would be to make vaccine distribution a routine part of treatment for the thousands of koalas brought into care centers every year after they are injured by cars or dogs, Dr. Timms said.

Many experts believe this vaccine would be an important step in helping koalas survive longer, perhaps buying enough time for researchers to solve some of the other problems they face. "In situations where you combine habitat pressure, domestic dog attacks and car hits with severe chlamydial disease, the outcome for koalas is devastating," Dr. Gillett said.

The New York Times

(China Daily 03/04/2012 page12)