From friend to family

|

|

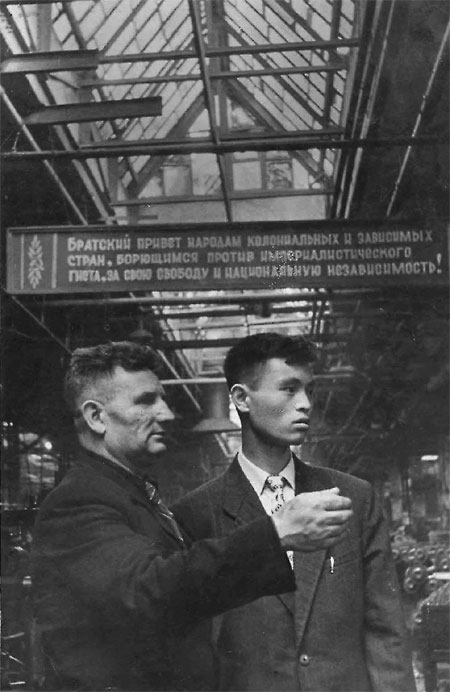

Manahov Ivanovic shows Le Minqiang around at the Stalin Automobile Factory in the former Soviet Union. Provided to China Daily |

A Chinese autoworker's friendship with his Russian mentor personifies the big picture of Sino-Russian ties. Zhu Zhou reports in Changchun.

Le Minqiang has been retired for almost 20 years. The 79-year-old lives with his wife in a small apartment not far from the headquarters of First Automotive Works (FAW) in Changchun, capital of Jilin province. Like many of his former co-workers, his whole family works - or at least did until retirement - for this automotive giant.

"This is my daughter's apartment. But we've been living here for 11 years now," the crop-haired Le says on a recent Sunday, sunshine streaming through the window.

This is a neighborhood of low-rises, "built in the 1980s", but some dorm buildings go as far back as the 1950s, when FAW was first established.

Le, a Shanghai native, came to Changchun in 1953, at the tender age of 20.

"I did not have much education, and I was working in a tool factory in Shanghai. It was an honor to be selected," he says.

China's first automobile manufacturer got off the ground with technical assistance from Soviet specialists.

"The Soviet experts said it is better you know how to do it than we send in special teams to do it for you every time. So, I was selected to become an intern at the Stalin Automobile Factory," Le recalls.

Before setting off for Moscow, Le went through six months' language training. Russian was hard, but he learned many technical terms, which came in handy when he later served as a translator for visiting Russian experts.

In June 1954, he arrived in Moscow. There, he met a person whom he would proudly call "my Russian father".

Manahov Ivanovic was a Soviet engineer with special expertise in grinding machines. After noticing Le had difficulty understanding Russian instructions, he showed "patience and kindness in teaching me".

Later, Le found out that Ivanovic's daughter, "of the same age as me", had died a year earlier in a stampede to pay tribute to Joseph Stalin's body.

"It was very sad, and I somehow reminded him of his only child," Le says.

"He gave me a Russian name, Misha, which I used during my year in the Soviet Union."

When a colleague suggested that Le should become Ivanovic's "godson", Le gladly said yes. Ivanovic was so elated that tears rolled down his cheeks, while he murmured, "My son! My son!"

For the May Day holiday of 1955, Ivanovic took his Chinese godson to his wife.

Many neighbors showed up as well.

"They wanted to see what his Chinese son looked like," he recalls.

Their friendship even caught the attention of Pravda, the official newspaper of the Soviet Union, which sent a reporter to cover the story and take photographs.

After Le returned to China, he began to apply what he learned in Moscow to his work. His workshop had 50 grinders that needed to be set up and adjusted. Because many workers had never worked on the equipment, they required constant technical support from Le.

One day, Le was informed that another batch of Soviet experts had arrived to help solve the problems.

Among them was his "godfather" Ivanovic.

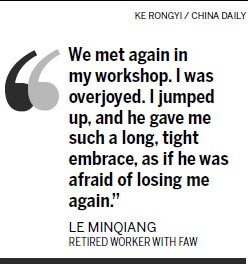

"We met again in my workshop. I was overjoyed. I jumped up, and he gave me such a long, tight embrace, as if he was afraid of losing me again."

During Ivanovic's stay in Changchun, Le became his assistant and translated for him.

They also worked in the engine workshop and calibrated machines for manufacturing pistons. With Soviet help, parts were produced that measured up to the set standard.

On July 15, 1956, the first Chinese automobile, a Liberation-branded truck, rolled off the assembly line.

"Some of the credit should go to those Soviet specialists who offered help," Le says.

But with the mission accomplished, they were bound for home. Ivanovic was also to leave. Upon learning his 50th birthday was approaching, someone suggested: "Your godson should throw you a birthday party."

This idea got to the top leadership of the factory. A film crew was invited.

When Ivanovic showed up at the scene, he was dumbfounded at the table full of peaches, noodles and red candles.

"I explained to him that this was the Chinese ritual for the younger generation to show love to their elders," Le says.

"The items were symbols of longevity. Tears welled up when he heard my explanation. He said 'Thank you!" and saved some of the food, saying he would show it to his family and friends in Moscow."

After the film crew left, the atmosphere became less formal. Le served dumplings, but Ivanovic was not good with chopsticks.

"I said: 'You taught me how to attune a grinding machine, and I now teach you how to train your hands to use chopsticks'."

The next day, they went to the factory and took some photos together.

"We kept corresponding for some time after he went back," Le says.

But the Sino-Soviet relationship took a nosedive after that.

Grassroots friendships like theirs became hard to maintain in that era of political repercussions.

"In 1962, it thawed a little," Le recalls.

A journalist from a literary magazine in Shanghai, who had previously interviewed both Le and Ivanovic in Changchun, traveled to Moscow. The factory had changed its name, but the Chinese reporter tracked down Ivanovic at his home.

"He was doing OK," Le says.

"But after that, we lost contact."

The unique friendship between a Chinese autoworker and a Soviet engineer lasted less than a decade, falling victim to political caprices of the day.

"If he were alive today, he would be 106 years old," Le says, with a tinge of sadness.

The Le family named their daughter Sasa, which sounds like Misha, the pet name given by "my Russian father".

Le was one of 560 Chinese autoworkers from FAW who "interned" at the Stalin Factory.

The most famous graduate was Jiang Zemin, who went on to become China's president. "He calls me Little Lezi," Le says.

- Russian, Polish fans clash before Euro 2012 match

- Russian side just too good, says Bilek

- Alibaba to accept Russian online payments

- Gourmet food of Russia

- Guangxi touts new tourism routes in Russia

- From Russia, with ballet

- China and Russia forum discusses the arts

- Harbin to celebrate tourism year of Russia

- Miss Russia 2011

- From Russia and Ghana with love, and designer funk

- Russia lures Hollywood, raising bar for local film