Overseas students at Tibet University study the local language in the autonomous region. Yang Shizhong / China Daily

The first dictionaries of the country's myriad ethnic languages without native written forms are rolling off the presses. As the foundations of the Middle Kingdom's Tower of Babel weaken, the structures to preserve these tongues have been building up. Deng Zhangyu reports.

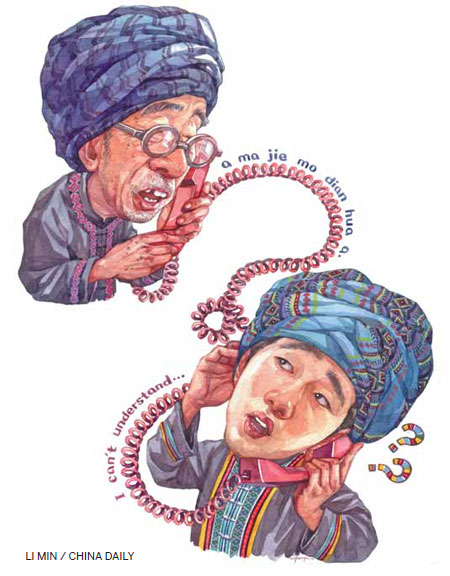

Tian Desheng is worried about publishing the Tujia-Han dictionary he has worked on for a decade. The 81-year-old says that's because his ethnically Tujia 20-year-old grandson speaks Putonghua, English and German but not a word of Tujia. Once Tian called his grandson and asked him in Tujia to put his grandmother on the phone. But his grandson required Tian to repeat the request in Putonghua because he couldn't understand his grandpa at all. The grandson's situation is typical, despite the fact the ethnicity is China's seventh largest with 8 million members.

Tian, who has spent his life studying and protecting his mother tongue, laments that only people around his age speak the language.

Younger generations in Hunan province's Xiangxi Tujia and Miao autonomous prefecture, where Tian lives, mostly communicate in Putonghua.

"I'm afraid nobody will know Tujia after old people like me die," Tian says.

That's why he invested a chunk of his life in the dictionary.?

The Tujia aren't the only Chinese ethnicity whose language faces extinction. Nearly all 55 non-Han groups' more than 130 languages face the same problem. (Ethnic Han account for more than 90 percent of the country's people.)

The risks are most accelerated for groups with smaller populations.

But governments, scholars and educated ethnic people are working harder than ever to preserve these languages, mostly by creating some of their first dictionaries.

While Tibetans, Mongolians and Uygurs have their own scripts, most of China's ethnicities only have spoken forms, including groups with millions of members like the Miao and Tujia.

Their words are codified using the International Phonetic Alphabet for tones and Chinese pinyin for spellings.

The country has been compiling ethnic languages since the 1950s. But investments have increased in recent years, resulting in newfound enthusiasm among scholars and local governments.

|

|

Tujia singers and dancers perform during the Lantern Festival in Hubei province's Yichang in 2014. The protection of ethnic cultures is a national focus. Ren Weihong / for China Daily |

Linguist Sun Hongkai, who has been involved in compiling more than 20 ethnic-language dictionaries, says: "A good dictionary requires several million yuan and many years. Many scholars and educated ethnic people are more than willing to do the work."

The 80-year-old has received many invitations by ethnic areas' local governments in recent years. Most want Sun to lead their dictionaries' compilation.

"They're increasingly aware of their identities," Sun says.

"They worry their unique cultures will be forgotten once their languages are."

Ethnic Miao Long Shengguang spent 14 years compiling his Miao-Han Dictionary that was published last year.

The 59-year-old Luquan Yi and Miao autonomous prefecture native says his sense of identity motivated him to undertake the project to preserve his ethnicity's language and culture.

It usually takes more than a decade for an individual or a team to create a dictionary of more than 10,000 words.

To collect as many words as possible, Long listened to the accounts of the elders, whom he says can tell stories day and night. The stories are wells from which new words can be drawn for codification.

He learned plant names from herbalists, animal words from hunters and textile terminology from weavers.

Long received 200,000 yuan ($32,020) from a local government cultural affairs body to finish his dictionary.

Tian is still seeking funding.

Tian shares anecdotes about mistakes made when Tujia people apply for IDs. Because many elderly Tujia don't know their names in standard Chinese, they're often registered according to Chinese-character transliterations.

For instance, a Miao person with a surname meaning "stone" (shi in Chinese) was registered with the Chinese character for ya (duck). Tian says such mistakes are common.

Sun points out language study goes beyond preserving tongues to also understanding their origins.

For instance, the language of the Dulong people, who dwell in remote mountainous areas and are known among outsiders for the vanishing tradition of tattooing women's faces, has changed little over a long time.

The Sino-Tibetan language family sub-group spoken by the ethnicity with fewer than 7,000 members, like many other ethnic languages, has no tones. But Putonghua has four. This shows how languages evolved, Sun says.

Sun says many foreign scholars learn standard Chinese and then learn ethnic languages. That's why it's easy to find foreigners in China's ethnic areas.

"Linguistics has no boundaries," Sun says. "China has 30 to 40 minority languages spoken across borders."

And many people, especially those codifying these tongues, hope this remains the case.