For many, Chinese dream means happiness

Psychological studies

There is a clear limit to the extent to which societies can become happier through the simple expedient of economic growth, a view borne out by a number of psychological and sociological studies of happiness conducted during the past three decades.

Rather, prosperity has to be shared more evenly and equitably, and there has to be greater social trust and greater confidence in the government, less corruption in business and official circles, fewer materialistic values, more freedom to choose what one does with one's life, better education for the whole population, and a number of other factors.

Happier people can promote better economic growth. Happiness at work is one of the main driving forces behind positive outcomes in the workplace, rather than just being a resultant product, as studies have widely proved.

The determination of Chinese people to achieve happiness can be uplifting. There has long been a cultural difference between East and West about the definition of happiness, and traditional thoughts about the emotion were quite heavy-hearted.

The ancient Chinese concept closest to happiness is probably that of fu. When the character was inscribed on oracle bones during the Shang Dynasty (c. 16th-11th century BC), it meant "to fill a wine jug at the altar and provide sustenance for a god", although according to the early 2nd century dictionary Shuowen Jiezi or Explaining and Analyzing Characters, it equated to "worshipping a god".

A far more worldly definition was given in the Shang Shu, or The Book of Documents, a compilation of historical documents from before the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC). In those days, fu included concepts such as "longevity, prosperity, health, peace, virtue and a comfortable death".

Confucius (551-479 BC) did not talk about fu; in fact, there's not a single mention of the concept in The Book of Conversations, the dialogues between the great sage and his disciples, according to Luo Lu, a professor at the National Taiwan University in Taipei, in a study of folk psychology.

Ritual, or li, was valued much more than mundane happiness. As dictated by tradition, even today the Chinese often value an alternative way of feeling satisfied.

"Human desires can be fulfilled through driving oneself hard and persistently striving, things that are valued highly in Western culture; or desires can be eliminated through even harder suppression and self-cultivation.

"When a simple lifestyle is adopted, the mind is cleared and a state of 'desirelessness' finally breaks the vicious circle of the reproduction of desires, frustration, and misery," wrote Luo.

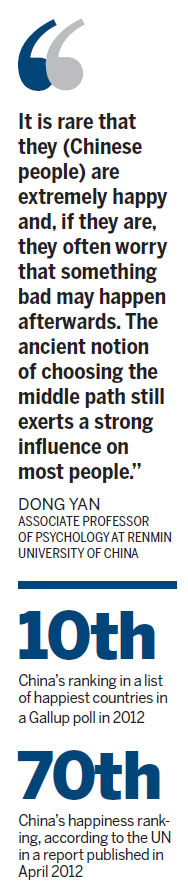

In mood studies, Chinese participants often report a lower level of happiness than Westerners, according to Dong Yan, an associate professor of psychology at Renmin University of China in Beijing.

"It is rare that they are extremely happy and, if they are, they often worry that something bad may happen afterwards. The ancient notion of choosing the middle path still exerts a strong influence on most people," said Dong.

In cyber life, especially on social networks, the Chinese appear to be much happier. However, "it can often happen that when a smiling face is typed, the person in front of the computer is expressionless; it's only when a laughing face appears, that she may crack a slight smile," she said.

The difference exists because the Chinese think of their feelings more in the context of social relationships and may want to entertain the people they are talking with on the Internet, she explained.

Registration Number: 130349