Society

Debate works up retirement policy

By Zhou Wenting (China Daily)

Updated: 2011-03-16 07:49

|

Large Medium Small |

|

Women produce clothes exported to Southeast Asian countries at a factory in Huaibei city, Anhui province. Some experts and officials consider the possible change in retirement age as a way to improve the rights of women, who retire five or 10 years earlier than men under current policy. Woo He/For China Daily |

Xu Zhiqing, 50, is fretful these days. She looks forward to retiring in five years, as current regulations require, but is bothered by the possibility that the retirement age will be pushed back.

|

||||

Delayed retirement became a hot topic after Wang Xiaochu, vice-minister of human resources, said in September that the ministry was considering the idea. He made the remarks at a news conference and said any decision would depend on China's population and employment outlook.

The issue was discussed recently during interviews with delegates to the just-concluded annual sessions of the National People's Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) National Committee.

What would delaying retirement mean in China? Proponents believe it is necessary because of the aging population and will benefit women, who retire five or 10 years before men. Opponents fear it would aggravate employment difficulties and widen the rich-poor divide.

|

|

China's retirement policy dates to 1951, when the central government set 60 as the retirement age for men and 50 for women. Modifications made in 1955 declared that men would retire at 60, female public servants at 55 and other women in the work force at 50. A 1978 document carried on those modifications, and they stand today.

But people live much longer now. Life expectancy at birth was just 46 years in 1950 and hit 73 two years ago, according to the National Bureau of Statistics.

As a result, it is reasonable to increase retirement age to 63-65 for women and men, said Hu Angang, director of the Tsinghua University's research center for contemporary China in Beijing. Not all experts agree.

A recent book, Reform and Development Strategies of China's Social Security, noted that post-retirement life has been prolonged by the increase in life expectancy. It looked at this phenomenon in terms, among others, of the economy and the structure of the labor force, pensions and the economy overall, return on the investment in human capital, and fairness.

More than 200 scholars and officials participated in study and discussion for the book, and more than 30 experts cooperated in writing different chapters.

One of them is Mu Huaizhong, vice-chancellor of Liaoning University and director of the university's population research institute. Mu cited labor force structure as a principle reason to support postponed retirement.

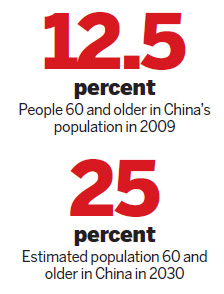

According to the 2009 Statistical Communique of China's Aging Development, the most recent data available, people 60 and older make up 12.5 percent of China's population. In 2030, they will be one-fourth of the total.

|

Zhang Hai'e, 53, an amateur model, practises catwalk moves with her partners from Luoyang college for senior citizens in Henan province. Women can enjoy a colorful life after retirement. Zhao Xiaoli/For China Daily

|

Taxes from slightly more than three working people support each pensioner now, according to the 2009 White Book of China's Manpower Resource. In 2035, only two workers will provide that support.

According to Mu's calculation, the size of China's work force will begin to decline in 2013. The ratio of workers to retirees already has dropped from 10-to-1 in 1982 to 3.5-to-1 in 2002.

"Can a young working force, which is much smaller in size due to the one-child policy, afford the pensions for the Chinese baby boomers?" Mu asked. The baby boom in China covers those born from the 1950s through the 1970s.

Critics said it's up to the government to provide for the aged. But Hu Xingdou, a professor of economics at the Beijing Institute of Technology, said China's input in pensions has long been insufficient.

"The country's social security fund accounts for 6 percent of gross domestic product, while the figure is 40 percent in developed countries," Hu said.

Tang Jun, deputy director of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences' research center of social policy, said it's not a simple act of collecting money and giving it out.

"Pension relates to a country's economic situation," Tang said. "If the money is invested properly, good profit will keep the pension alive."

More or fewer jobs?

Many countries have pushed back their retirement ages to cope with an aging population and the lack of labor supply. China's population is getting older, too, but some sociologists argue the country's work force is already more than sufficient.

According to Tang Jun's calculations, 20 million people enter the non-farming work force each year, but they compete for only 10 million open jobs. "So the longer seniors remain in their positions, the less room there is for the young."

Zhou Xiaozheng, a professor of sociology at Renmin University of China, said, "Retirees emit afterheat, but college graduates are at the peak of heat.

"The unemployment rate of college graduates in 2009 was 13 percent. If the figure grows higher, social stability will be threatened."

|

|

Fan Ming, director of Henan University of Economics and Law's institute of market economy, has a different view.

China's 2000 census found that one-third of pensioners were re-employed at new jobs, Fan said, "and the actual figure might be 76 percent, so no so-called vacancies will be left because of retirement. In other words, delayed retirement doesn't influence the employment rate".

He compared retirement ages and unemployment rates for 91 countries and regions in 2009, and found that countries with higher retirement ages also had better employment rates.

Fan also said that when people start taking a pension, which is almost half of their working income, their spending power decreases and, with it, their demand for consumer goods. When fewer products are sold, factory orders decline and the demand for labor decreases. The longer people stay in the work force, Fan said, the longer they sustain the need for labor.

"So taking the long view, we believe increasing the retirement age will help improve the employment situation rather than worsen it," Fan said.

A matter of fairness

A report in late February by the NPC Standing Committee cast the possible change in retirement age as a way to improve the rights of women, who retire five or 10 years earlier than men under current policy.

That drew applause from some gender studies experts, who complained the current provision impairs women's promotion prospects and harms those who are willing and able to keep working.

"When a superior considers a promotion for two candidates, say, a man and a woman who are both 50 years old, the woman is probably at a disadvantage because she is approaching the expiration date for work," said Li Xia, an anthropologist specializing in women's studies and senior editor of the Commercial Press.

Liaoning University's Mu Huaizhong said, "Senior experts, especially women, who retire at 55 don't even have time to earn back the tuition for a doctorate." It was humorous, but not a joke.

A recent four-year study that Tang Jun conducted in Henan, Zhejiang and Sichuan provinces and Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region found that most women don't want their working years to be prolonged.

"No one, among the 3,000 women residents and migrant workers interviewed including doctors and technical staff, would like to retire at age 60 like men, " Tang said. "Instead, most of them said they can't go on working if the retirement age is delayed."

|

|

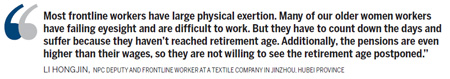

Tang said every country, when considering adjusting retirement age, faces the same problem: Senior technical staff and others who enjoy good social welfare appreciate it, and low-end laborers reject it.

Sociology experts said the intensity and duration of blue-collar work is already unbearable. The current actual retirement age on average is 53, and early retirement is common, especially in small cities.

Last year, a series of protest demonstrations were called in France when the country lifted its retirement age from 60 to 62. "China might suffer more serious political risks," Tang said, "for 70 percent of laborers in the country are blue-collar workers. The percentage is much higher than in Western countries."

Tang also mentioned the 30 million people who were laid off in the 1990s. They're nearing retirement age, and their pensions would provide more income than the unemployment compensation they've been receiving. Waiting a further 10 years would not be well received, Tang said.

"Like Premier Wen Jiabao said, 'Social equity and justice can shine even brighter than the sun'. We don't fear scarcity but uneven distribution," said Zhou at Renmin University. "The government should consider the issue prudently, for it relates to the most vital interests of the masses."

Most experts interviewed by China Daily said it is too early to discuss pushing back retirement age, and that the country can adopt a flexible retirement policy in the future if it encounters a labor shortage.

| 分享按鈕 |