Profiles

'China's Schindler': A daughter remembers

By Ho Manli (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-04-05 09:51

|

Large Medium Small |

The ancient Chinese said, "樹高千丈, 葉落歸根", meaning, "A tree may grow to be a thousand zhang (10,000 feet) high, but its leaves fall back to its roots".

So it was with my father. In 2007, 10 years after his death, I brought his and my mother's ashes back from the United States for burial in China, fulfilling my father's wish to be laid to rest in his native soil.

Since then, I have crossed the Pacific every year to sao mu - to sweep my parents' grave - in the city of Yiyang in Hunan province. For the past two years, it has been on Qingming Festival, observed today this year. The date marks the traditional grave-sweeping festival, when Chinese pay homage to their ancestors.

|

|

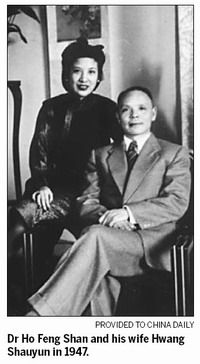

Every year I am joined by many others - officials, schoolchildren and local citizens - in honoring my father, Dr Ho Feng Shan (1901-97), the Chinese diplomat and rescuer of thousands of Jews in Austria. He is popularly known as "China's Schindler" and is Yiyang's most famous native son.

For his final homecoming in 2007, the city held a commemoration, which included the unveiling of a new gravesite on beautiful Huilongshan Park. The ceremony was attended by hundreds of people - city and provincial officials, Jewish community members from Shanghai, and the then freshly arrived Israeli ambassador to China, Amos Nadai. In 2000, his country had designated my father a "Righteous Among the Nations" for his "humanitarian courage" in saving Jews in Austria on the eve of World War II.

Days earlier, I had held a small private interment ceremony with family members and the few city officials most directly involved in arranging for my parents to be buried in Yiyang. To me, it was the culmination of three years of hard work, from finding and negotiating a suitable site with good fengshui to the design and building of the grave.

My father had wanted to be buried in the Taohualun section of Yiyang, where he had spent his childhood.

Taohualun, or Peach Blossom Village, had been a hilly and verdant oasis during my father's time. It is now completely urbanized. Its rolling hills have been flattened to accommodate wide boulevards and big buildings, including those of the municipal government. There was, however, a small range of hills that overlook Taohualun named Huilongshan - Meeting Dragon Mountain. It has long been a public park - with an old wooden carousel on one of its peaks - but in recent years most of it has become a Buddhist retreat.

After settling on a possible site on one of the peaks, I petitioned the city and was granted permission for a gravesite in Huilongshan Park.

There was then the question of designing a grave. I wanted a grave for my parents that would impart a sense of peace and tranquility. It should reflect my father's fierce love of China and his worldly career, and that would convey my mother's love of beauty and her exquisite sense of aesthetics. I knew, with mixed feelings, that the price of having my parents buried in Yiyang was that this would not be a private family grave. It would also be a public monument.

Many local designs were submitted to the city. Some were monumental - one looked like a giant Mayan pyramid with a waterfall - others appalling.

One bristled with carved winged columns; it was submitted by a manufacturer of said columns. Some were comical.

The favorite of one city official was a pointy white pole next to a wavy white marble rectangle on a platform. It took a while to figure out that this was meant to represent a pen, and one of the visas my father had handed out to save Jews.

Luckily, I was able to turn to the Chinese-American architect Wenyi Wu, whose family, originally from Yiyang, has been friends of ours for two generations. His design fulfilled all the elements I had envisioned for my parents' final resting place and satisfied the city fathers as a fitting and unique monument.

And it is unique, as it combines East and West. The dark green granite tombstone sits on top of a stylized version of the traditional Chinese burial mound. The mound has three concentric rings, with the innermost representing home, the middle representing country and the outer representing the world.

Encircling the back of the tomb is an inner wall of white marble with two black stone insets. One is carved with an epitaph written by the renowned Chinese writer Yu Qiuyu and the other a poem written by my father and dedicated to my mother.

The tomb is in a small cobblestone open area flanked by a high Middle-Eastern style outer wall made of local river stones on one side, and a low wall of rough-hewn stone slabs on the other, providing seating for rest and contemplation.

When it all finally came together, I was still torn about leaving my parents in such a faraway place.

On the day of their interment, as we were about to place their urns into the ground, two large yellow and black butterflies suddenly appeared and flitted about in tandem before disappearing.

The locals were agog and elated. Although wooded, there were no flowers on Huilongshan so butterflies were never seen there, they said. It was a sign, they said.

So it appears, as I have followed suit and come every year, climbed the 137 stone steps up the mountain bearing flowers, incense and firecrackers to sao mu at my parents' grave.

For China Daily