Exhibition examines French impressionist artist's rendezvous with Asian palette

While audiences may be familiar with Mary Cassatt's tender depictions of mothers and children, a new exhibition in San Francisco aims to unveil the "radical" approach of this American impressionist and her embrace of Asian art as inspiration.

Mary Cassatt at Work, a major exhibition at the Legion of Honor museum, invites viewers to look at familiar images with fresh eyes and explore the cross-cultural influence on Cassatt's artistic creations.

This exhibition, running till Jan 26, features over 90 works by the artist, including oil paintings, pastel drawings and woodblock prints on loan from various institutions across the United States.

The first North American retrospective of Cassatt's work in 25 years, it offers a unique opportunity to explore the artistry of Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), a leading figure of the French impressionist movement and the most celebrated female artist of her era.

The moments depicted by Cassatt, such as women knitting and needlepointing, bathing children and nursing infants, may not seem "radical" today because people are "so used to the ubiquity of instantaneous images", says Thomas P. Campbell, director and CEO of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, which comprises the Legion of Honor and the de Young.

"When she was working, such images were not instantaneous — even photographs required long exposures — so the moments of tenderness that she captured were groundbreaking in her time," says Campbell.

The exhibition aims to showcase the experimental and innovative techniques that earned Cassatt the distinction of being the only American artist included in the first impressionist exhibition 150 years ago in 1874, he adds.

The exhibition shows Cassatt's multifaceted exploration of modern life, particularly focusing on the roles and inner worlds of women and children during the late 19th century.

It begins with groundbreaking impressionist works portraying women in the audience at the Paris Opera. Moving through Cassatt's career, the exhibition includes depictions of bourgeois women engaged in various tasks, acute portrayals of children and revolutionary color etchings inspired by Japanese woodblock prints.

Organizing curator Emily A. Beeny encouraged visitors to "look with fresh eyes at familiar works of art and excavate the original radicalism of Cassatt's working methods".

Born into a wealthy family in Pennsylvania in the US in 1844, Cassatt defied the norms of her social class by pursuing art as a profession rather than a genteel accomplishment. She began her formal training at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts as a teenager and continued her studies in Paris under renowned academic masters.

It's in the early 1880s that she began to turn to the theme of mother and children. By the turn of the 20th century, with the exception of a few portraits, she painted little else, says Beeny.

Beeny says that Cassatt was also a "path breaker" in terms of subject matter. In the early 1880s, Cassatt began to focus on mother and child scenes, a theme that would dominate her work by the turn of the 20th century.

It was the first time in Western art that an artist had captured the "deep insight and sympathy into the inner lives of children" and the work involved in caring for them, Beeny says.

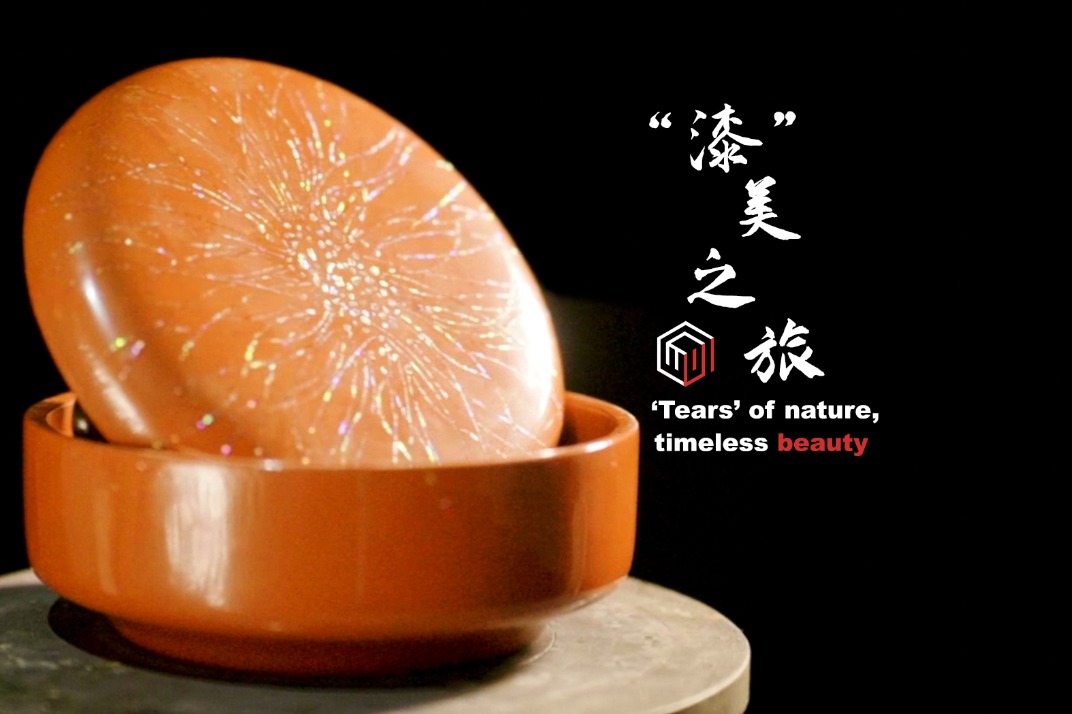

The exhibition also sheds light on Cassatt's exploration of woodblock printing, an art form that originated in China during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and later spread to Japan.

This aspect of her work represents an example of East-West cultural exchange, she notes, as the opening of Japan to global trade in the 1860s led to an influx of Japanese prints in the West, profoundly inspiring Cassatt and her contemporaries.

Beeny says she saw the enduring influence of East-West cultural exchange in artistic creation.

"Our recent exhibition program at the Legion of Honor is a testament to that. And I think we are increasingly looking for opportunities in our permanent collection to highlight those connections — for example, some of the beautiful Chinese porcelains that received French gilt bronze mounts in the 18th century that we have on display, and the imitations of Asian lacquerware that we find in British galleries. There are many connections between the East and the West," she told China Daily.

"As we continue refreshing and revising how we think about the permanent collection, we're really looking for ways to highlight those connections between the East and the West," Beeny says.