New flight trajectory for bird origins

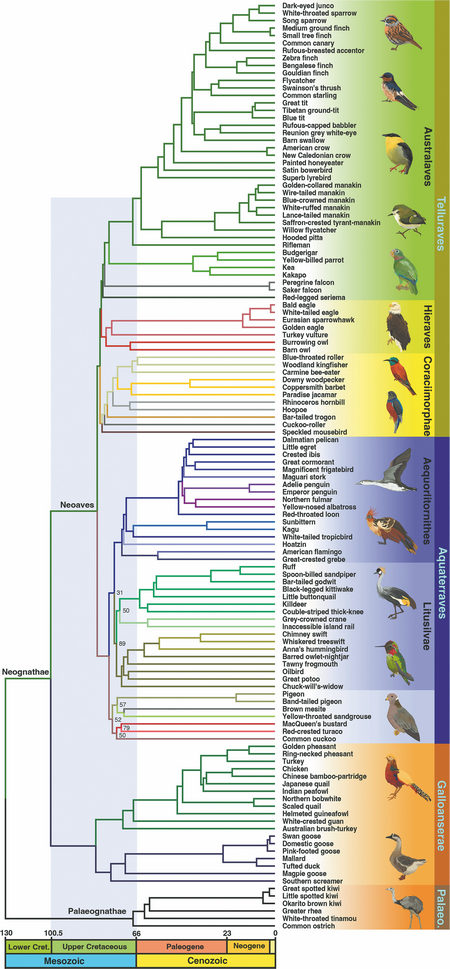

The researchers extracted DNA-sequence data from 25,640 genetic loci, referred to fossil records from different geological periods, and reconstructed the evolutionary history and trajectory of modern birds through phylogenetic tree construction, molecular clock estimation and species diversity differentiation rate analyses.

The scientists estimated when the branches split into new lineages by comparing the mutations that accumulated along the branches. The older the split between two branches, the more mutations each lineage built up.

"Remarkably, these two major bird lineages diverged during the Late Cretaceous Period — long before the famous dinosaur extinction event," Wu says.

"Our study indicates that the radiation (divergence out from a central point) of modern birds was in remarkable lockstep with that of flowering plants and other organisms."

Traditional theories have long linked the evolutionary history of modern birds to the mass extinction event around 66 million years ago, suggesting that they evolved rapidly after the dinosaurs vanished.

However, the research indicates that the mass extinction event did not have a significant impact on the evolution of modern birds. Instead, the global warming event that occurred around 55 million years ago, known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, led to the turnover of modern marine bird evolution, a process by which species in a particular ecological niche or geographic area are replaced by new species.

"It has thus challenged our traditional understanding that modern bird origins can actually be traced back to the dinosaur era," Wu says.

The findings were published on Feb 12 in the paper Genomes, Fossils, and the Concurrent Rise of Modern Birds and Flowering Plants in the Late Cretaceous, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States, a peer reviewed journal of the National Academy of Sciences.

"I imagine this will ruffle a few feathers," The New York Times quoted Scott Edwards, an evolutionary biologist at Harvard and one of the study's authors, as saying.

Scientists in various fields in both countries took part in the project out of their shared interest in birds, according to Wu.

The team included prominent researchers like Zhou Zhonghe from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology affiliated with the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Edwards from Harvard and Liu Liang from the University of Georgia.

Wu had previously examined genomic data with US scientists to understand species' origins and relationships when he was a college student.

Similar studies have been conducted on mammals and angiosperm (flowering plants), both of which Wu says account for a big part of biodiversity in the Cenozoic, Earth's current geological era.

"Everyone played a crucial role in the project," Wu says. "The scientists from abroad came to China to engage in academic exchanges with us, and discussions were direct and sparkling."