Circles of influence

Fang believes that he has found that missing link. "From Hongshan to Songze, there had always been two-dimensional representations of the three-dimensional jade dragons. Of them, some amounted to frontal views," he says.

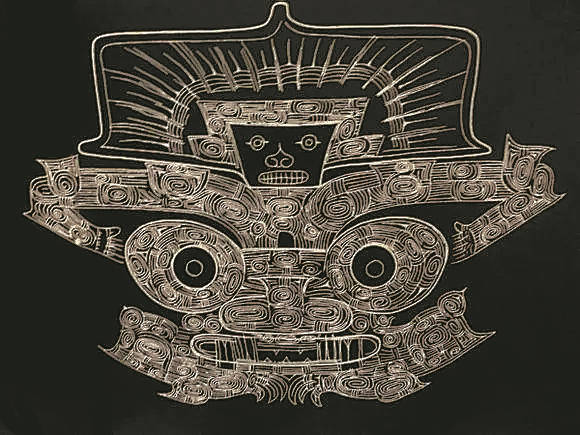

That's where the beast on the green-colored, bracelet-shaped cong fits into the narration: It is very likely to be a head-on view of a dragon, with the same big eyes defined by concentric circles. While the long snout has inevitably become less obvious, the same perspective serves to underscore the wide mouth, which eventually took its bar-like shape.

The direction this image was heading has been pointed out by another bracelet-shaped cong, this one with a pale grayish color, that is currently displayed side by side with the green one at the Shanghai exhibition. Here, it is clear that the beast had gone through certain changes, which allowed it to move further away from the dragon it once was and nudge closer to the beast it were to become.

Compared with the green one, this grayish cong, although still dated to early phase of the Liangzhu civilization, was unearthed in the Yaoshan Altar at the Liangzhu Ruins, that is, much closer to the heart of the civilization.

It would take roughly another 300 years for the Fanshan Cemetery and the palatial compound to be built, 5 km southwest of Yaoshan, in around 3000 BC, and for Liangzhu jadeware production to reach its pinnacle.

In the meantime, the bracelet cong, whose shape evokes those wide bracelets unearthed from Lingjiatan, would evolve into a much more sophisticated shape, made up of a cylindrical tube encased in a square prism. For its part, the man-and-beast pattern appears on the prism's four vertical sides, as well as its four vertical edges. In the case of the latter, the edges serve as an axis to the symmetrical patterns.

Wang Ningyuan, a leading archaeologist working at the Liangzhu site, serves up his own analysis. "There's a possibility that the edge represents the imaginary line that runs through a person's face, from the middle of the forehead to the chin," he says. "This line, which coincides with the nose ridge, can be emphasized to a degree where it becomes an edge, and a divider."

The divided halves, miraculously, present two side views of the same beast, pointing archaeologists in new directions.

"It has long been suggested that Liangzhu's beast may have given rise to the image of taotie, a demonic creature commonly emblazoned on the ritual bronzes of the Shang (c. 16th century-11th century BC) and Zhou (c. 11th century-256 BC) dynasties," says Fang. "Although any direct link has yet to be established, or is unlikely to be found in the near future, one thing stands up to bridge these two images.

"The taotie, being frontal and bilaterally symmetrical, could have been made up of the two side views of one creature. This opinion is supported, among other things, by how the creature positions its legs and claws," he continues. "And if you look at the Liangzhu beast really closely, you'll notice the same arrangement with its crouched legs and claws."