A philosophical approach

Modern drinkers owe much to Lu Yu, the 'tea saint', who unlocked the mysteries of China's signature beverage, Cheng Yuezhu reports.

"Served as a beverage, tea is best suited to those who uphold discipline and moral conduct," Lu wrote in The Classic of Tea, emphasizing the tea preparation and ritual, which helped elevate tea into a symbol of refinement and social status.

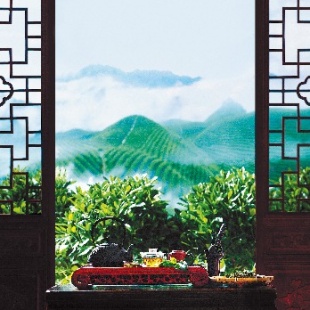

An exemplar among tea drinking rituals is the Jingshan Tea Ceremony, a solemn ceremony hosted at the Jingshan Temple in Yuhang district, Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, where Lu visited during his journey.

Though it is recorded that the temple's founder offered tea as a sacrifice to Buddha in the mid-Tang Dynasty, the ceremony became a mature practice during the Song Dynasty (960-1279), in which tea was relished by Buddhist monks and guests, the majority of whom were literati and bureaucrats.

Here, tea became a medium for meditation and enlightenment, which involved more than 10 formal procedures, including welcoming the guests, burning incense and paying tribute, as well as making and drinking the tea.

"The ceremony reflected the refined lifestyle of literati and bureaucrats from the Song Dynasty," says Yanping, a Buddhist monk at the temple and an inheritor of the art form.

"The senior monks of Jingshan Temple at the time wanted people to feel their own existence through relishing a cup of tea."

Contrary to contemporary tea drinking, habits of consuming a considerable amount within a short time, Yanping says that Song Dynasty attendees would usually savor one small cup in two hours in silence.