Companions in solitude

Wang Xizhi was born with a silver spoon in his mouth and never felt the need to worry about the more mundane matters in life; but there were others who had to toil to make ends meet while finding time to entertain their vision as a noble-minded recluse.

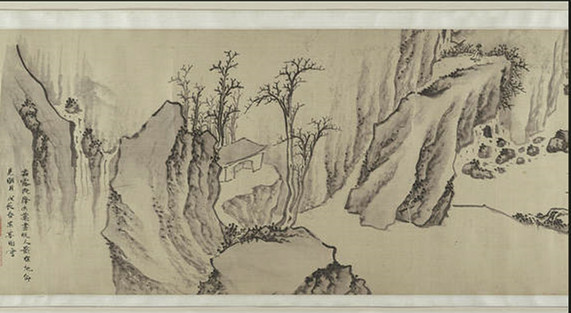

Shitao (original name: Zhu Ruoji), a much-revered 17th-century painter-recluse whose painting album is on display in the exhibition, complained later in life to a friend about having to labor on a commission of large-scale screens meant as home decor.

Talking of reality, in premodern China one group bound by reality to live rather secluded lives were women. Scheier-Dolberg gives space to that aspect by including images of aristocratic ladies seen in residential spaces, "heavily manicured" gardens, for example.

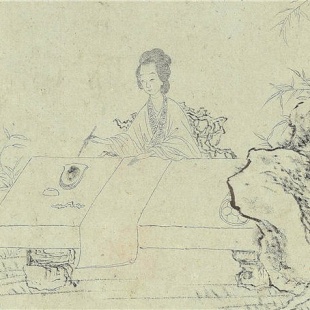

In 1799 a female scholar named Cao Zhenxiu wrote a cycle of 16 poems-all on famous women of history and legend-before commissioning a young painting virtuoso of her time, a man named Gaiqi, to provide illustrations. The result, on view in the exhibition, shed light on what Scheier-Dolberg called "an increasing participation of women in literary activities", exemplified by Cao, who, judging by the poems, clearly felt an affinity with her female predecessors in history.

Among them was Madam Wei Shuo, a maternal aunt of Wang Xizhi, who first taught him calligraphy.

The exhibition also features images of women enjoying their own elegant gatherings. Throughout premodern Chinese history such events largely existed in paintings or book pages, that is in the imagination of artists and writers, Wang Yimin said. This is not to include the get-togethers of wives and concubines of a powerful patriarch, which, by virtue of all the chess-playing, tea-savoring and string-plucking, resembled an elegant gathering.

"Even during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), a period characterized by a prosperous, open society, women were only allowed to attend gatherings accompanying their husbands," he said.

Although small in number, literally accomplished courtesans offered the most notable exceptions. Turning up at an elegant gathering not as the accessories of men, but as their counterparts-at least creatively, they left behind words that lasted as long as their legends.

Within that painting album by Shitao are two images of fishermen. Their existence, with that of the woodcutters, was long romanticized by the members of the literati class. Tempted to think that they might one day trade their living "at the whim of a massive bureaucracy", to quote Scheier-Dolberg, for one at the whim of nature, the scholars-officials embraced these men of hard labor as they did Tao Yuanming's chrysanthemums and thatched huts.

Sometimes just a fish might do. In 1082 the Song Dynasty (960-1279) literary giant Su Shi, after discovering that he still had wine and fish to offer, embarked on a nighttime escapade with friends. A more adventurous version of the elegant gathering, during which Su climbed to the top of a cliff to release a "primal scream", the event was recorded by Su in his literary masterpiece Second Ode on Red Cliff.