For city's darkest day, justice is still to be dispensed

The gallery, whose collection John Whittington Franklin has helped to build together with curator Paul Gardullo, also features a number of charred coins collected by young Monroe in the days and months after the massacre.

In an article written for the museum, Gardullo recounted how the boy was able to find solace from searching for coins left behind by the looters. The copper pennies, belonging to black families who preferred to keep their hard-earned wealth at home rather than in a white-owned bank, had withstood the heat of burning to offer a potent metaphor.

"The story is ultimately not about massacre but about the indomitable human spirit-perseverance, faith, hope and resilience," Johnson said, referring to qualities that he clearly sees as transmittable, although the transmission of wealth itself between different generations of African Americans had often been impeded by racially motivated violence.

Imbued with a sense of righteous defiance, black Tulsans rebuilt their homes to such a degree that the National Negro Business League held its 26th annual convention in Greenwood in 1925, the year B.C. Franklin got together with his family. The community peaked in the 1940s.

In the meantime, despite common belief, there had been, from the very beginning, sporadic but equally heroic efforts from black Tulsans to save the memory for later generations. One of them was Mary E. Jones, who was compelled by the massacre to become a journalist and author, before writing about her experience and that of others in the 1923 book Events of the Tulsa Disaster.

"I had no desire to flee," Jones said in her book. "I forgot about personal safety and was seized with an uncontrollable desire to see the outcome of the fray."

Another example involves William D. Williams, whose remarkable story is recounted in Gardullo's writing for the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Williams, the son of a black couple who owned Greenwood's iconic Dreamland Theater, lived in Tulsa in 1921. He later left for college, receiving letters from his mother telling him how hard it was to "pull out" and rebuild, physically and emotionally. The young man eventually returned to Tulsa to teach history at his alma mater, Booker T. Washington High School, where he developed his own curriculum on the massacre.

One of his students, Don Ross, later became an Oklahoma state representative and successfully lobbied to create the Tulsa Race Riot Commission.

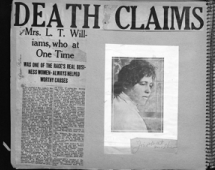

Williams died in 1984 aged 78, having assembled over the years a scrapbook that includes an obituary notice for his mother. The lady, despite all her effort to "pull out", died in a mental asylum in 1928, a victim of the massacre's long-term trauma.

"At every juncture, white Americans have taken whatever opportunities and success and ambition that black Americans have earned and destroyed it," said Jonathan Silvers, director of the documentary Tulsa: the Fire and the Forgotten, aired on the US channel PBS on May 31 to mark the massacre's centennial. Speaking at an online discussion on the massacre, Silvers said he was prompted to do the movie by a news story about "mass graves possibly discovered in Tulsa" in October 2019.