For city's darkest day, justice is still to be dispensed

Outside the courthouse, the white mob clashed with a group of blacks who marched there to protect Rowland and ensure he at least received a trial. A shot was fired and "things sort of went south from that point", Johnson said.

The white mob, armed and greatly outnumbering the blacks, shot its way through the Greenwood District, firing indiscriminatingly into businesses and residences. This was followed by looting and burning, which lasted for 16 hours until noon on June 1.

George Monroe, 5, was consumed by terror.

"All of a sudden my mother was excited because she saw four men coming toward our house," Monroe recalled in the mid-1990s. "All of them had torches, lighted torches on their side coming straight to our house. When these four men came in, they walked right past the bed, straight to the curtains in the house and they set fire to the curtains. As a result, everything in and around was burning."

All the time, Monroe was hiding under a bed with his older sister, who threw her hand over his mouth to stop him screaming when a rioter unknowingly stepped onto his finger.

Monroe waited for 75 years to tell his story: in 1996 the Tulsa Race Riot Commission, a state-sanctioned task force, was set up to investigate the massacre, and he was among the 108 survivors the commission ultimately located across the country.

Among other things, the commission found that the city had conspired with the white mob against its black citizens.

"We don't know of any approved incident where law enforcement officers were murdering people, but what we do know is that they deputized some people in the white mob and provided them with weapons," Johnson said. "The National Guard rounded up black people and put them in internment centers in the middle of the massacre. The stated purpose was to protect them, but we know from the survivors that what it did was to leave the Greenwood community largely defenseless."

According to the Tulsa Historical Society and Museum, more than 6,000 black people were held at one point, some for as long as eight days. After the massacre it was official policy to release a black detainee only upon the application of a white person.

However, in a report issued by the Tulsa City Commission two weeks after the massacre, Mayor T.D. Evans was unequivocal: "Let the blame for this negro uprising lie right where it belongs, on those armed negroes and their followers who started this trouble and who instigated it."

Last September a lawsuit was filed in the Oklahoma state court against the city of Tulsa by lawyers for the massacre victims and their descendants, including Fletcher, Ellis and Randle, whose appearance before the congressional subcommittee constituted part of that quest for delayed justice.

In 2007 the US Supreme Court upheld lower court rulings that a federal lawsuit seeking damages was barred by the statute of limitations, in effect telling the victims and their descendants that they were too late for any remedy.

Behind this prolonged fight is what many have called a conspiracy of silence.

Immediately after the massacre, all original copies of the issue of The Tulsa Tribune that seems to have incited the mob disappeared, apparently having been destroyed. The relevant page is even missing from the microfilm copy. According to a newspaper report at the time, Sarah Page, who left the town immediately after the massacre, later wrote a letter to the county prosecutor saying she did not want to press charges against Rowland.

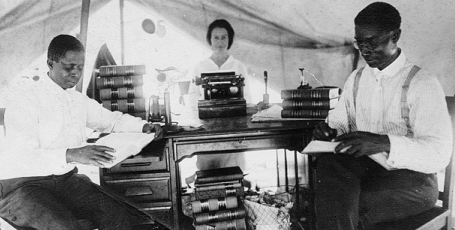

In fact, the most powerful indictment of the murderous mobs is in the form of picture postcards taken, most likely by its members, and widely distributed after the massacre as souvenirs of the prowess of white supremacy. These images, never showing the need to restrain from depicting bloodstained bodies of black Tulsans, feature captions such as "Negro slain in Tulsa riot", the word riot seen by many as an insidious effort to rewrite history by blaming the blacks.

Yet there is more to it. "If the damage was occasioned by riot or civil unrest, the insurance policy typically would not pay proceeds," Johnson said. "That's why labeling it as a riot was really important at the time.