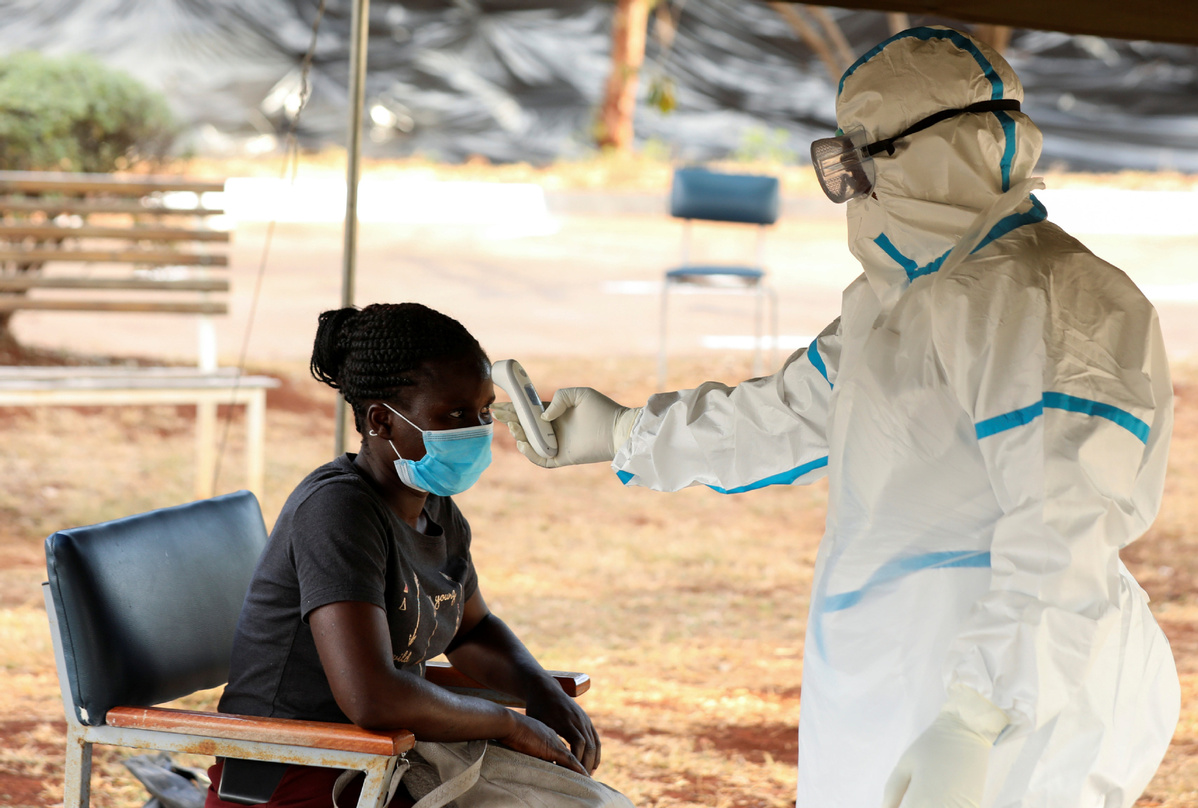

UN launches updated response plan to help fragile countries fight COVID-19

UNITED NATIONS -- The United Nations on Thursday launched an updated COVID-19 Global Humanitarian Response Plan that requires $6.69 billion to help fragile countries cope with the pandemic.

The fund requirement of the original response plan, which was launched on March 25, was $2 billion.

The updated plan is adding nine countries -- Benin, Djibouti, Liberia, Mozambique, Pakistan, the Philippines, Sierra Leone, Togo, Zimbabwe, bringing the total number to 63.

UN Undersecretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs Mark Lowcock, who launched the updated plan, said urgent action is needed to help the most vulnerable countries.

COVID-19 has now affected every country and almost every person on the planet. But the most devastating and destabilizing impacts will be felt in the world's poorest countries, Lowcock told a virtual event for the launch of the new appeal.

Apart from the direct health impact, the global recession and the domestic measures taken to contain the virus will take a heavy toll on the poorest countries, he said. "We can see right now incomes plummeting and jobs disappearing, food supplies falling and prices soaring, children missing vaccinations, meals and school."

He warned that the first peak of COVID-19 is expected in many of the poorest countries in the next three to six months.

The international community must be prepared for a rise in conflict, hunger, poverty and disease as economies contract, as export earnings, remittances and tourism disappear, and as health systems are put under strain, said Lowcock. "This cannot be business as usual. Extraordinary measures are needed, reflecting the extraordinary problem we face."

The updated response plan includes more of a focus on food insecurity, as well as how to help the most vulnerable and how to address gender-based violence, sexual exploitation and abuse.

Lockdowns and economic recession may mean a hunger pandemic ahead for millions. In many places, the impact of national measures to contain the spread of the virus and the global recession may be larger than the direct impact of the disease, said Lowcock.

"We must fight the disease, but in the poorest countries, it won't be the only battle we face. A coronavirus vaccine is essential, but it will not save a child starving to death."

If the international community does not act swiftly, it faces a reversal of the development gains that have been made over several decades, he warned.

The United Nations estimates that the cost of protecting the most vulnerable 10 percent of people in the world from the worst impacts is approximately $90 billion. That might sound like a lot. But it is equivalent to just 1 percent of the global stimulus package the world's richest countries have put in place to save the global economy, said Lowcock.

To meet these costs, wealthy countries will need to make significant one-time increases in their foreign aid commitments. And international financial institutions will need to change lending agreements with vulnerable countries, he said.

The alternative, said Lowcock, is dealing with the spill-over effects over many years to come. That would prove even more painful, and much more expensive -- for everyone.

"I urge donors to act with both empathy and in their own self-interest today," said Lowcock. "As the (UN) secretary-general has said, this pandemic threatens the whole of humanity. The whole of humanity must respond."

Lowcock was joined at the virtual event by UN High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi; World Food Programme Executive Director David Beasley; head of the World Health Organization's Health Emergencies, Mike Ryan; and the president and CEO of Oxfam America, Abby Maxman.