Canberra needs to rebuild trust with China

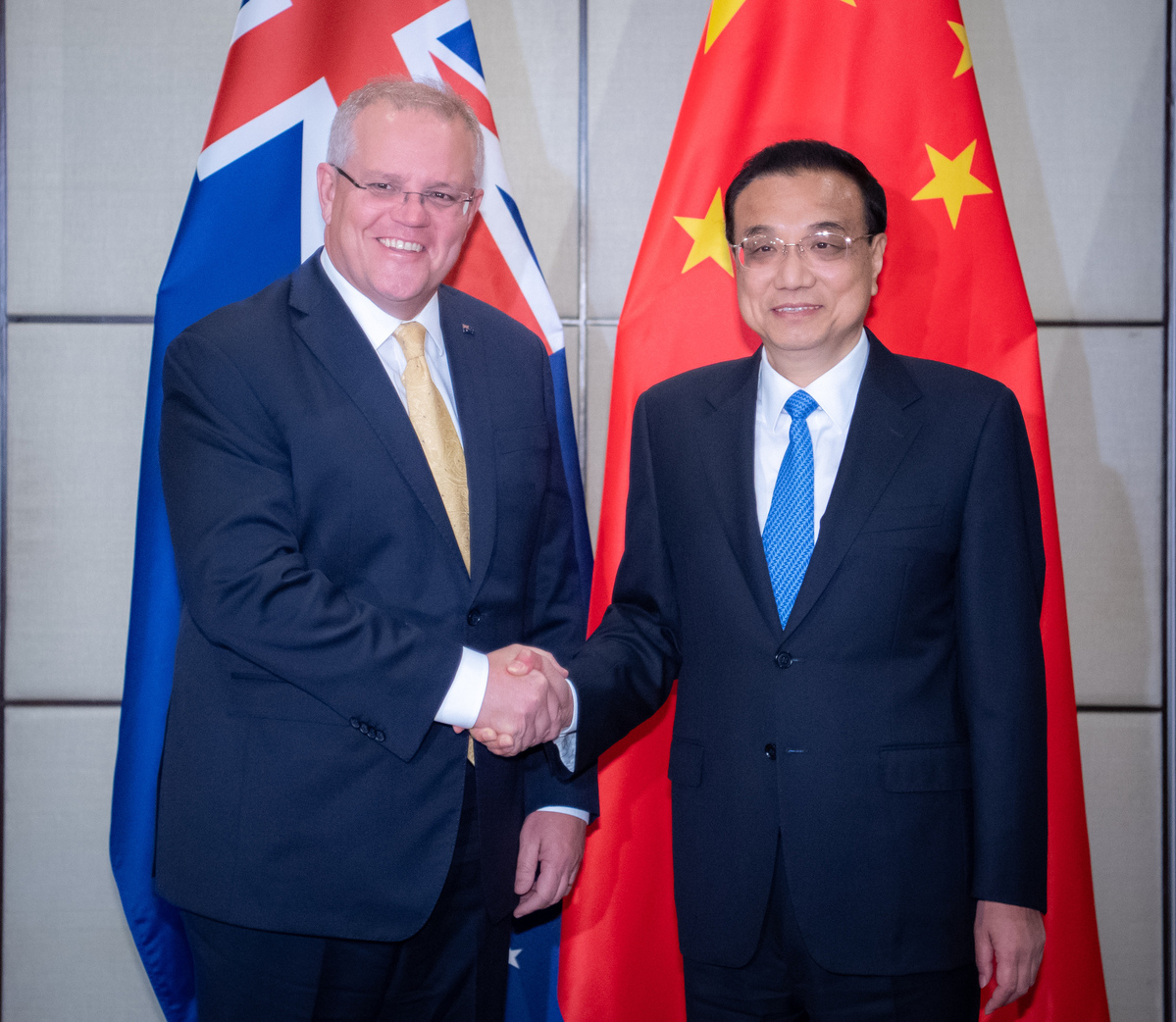

Don't read too much into the recent meeting in Bangkok between Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Premier Li Keqiang. It will take more than a 45-minute meeting to repair the strained relationship between the two countries.

Former trade minister Andrew Robb is on record describing the relationship with just one word: "toxic". Four years ago, he put the finishing touches on the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement. At that time, relations between Beijing and Canberra were on a more solid footing.

But relations have deteriorated to a point where one could be forgiven for thinking we are still back in the Cold War and not in the 21st century. Just listen to the rhetoric coming from some Australian politicians.

Earlier this year, Andrew Hastie, a Liberal member of Parliament and former officer in the elite Special Air Service, warned that Beijing's expansion into the region posed a "fundamental threat to Australia's economy and national security". He likened the world's approach to containing China to what he described as the "catastrophic failure" to prevent the rise of Nazi Germany.

His claims were rightly denounced by Beijing. The Australian prime minister, however, was reluctant to bring Hastie into line.

Last month, Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton launched a wide-ranging attack on the Communist Party of China, accusing it of being behind a series of cyberattacks on Australian sites, stealing intellectual property, and muzzling free speech at Australian universities. He didn't present one scrap of evidence to back the claims.

During his recent state visit to the United States, Morrison called on Beijing to give up its "developing nation" status, an issue that US President Donald Trump has been pushing for some time.

Australian Foreign Minister Marise Payne used a public forum to attack China on human rights. Australian universities have been questioned about their collaborations with Chinese universities, especially when it comes to technology.

China's role in the Pacific has been questioned, and technology giants such as Huawei have been banned. And the list of frictions goes on.

China has no problem with constructive dialogue as long as it is fair and balanced. It also prefers to have these conversations face to face, not conducted by the media or at public forums.

The prime minister may dismiss China's concerns over the strained relationship, arguing that it is "built on honesty about their differences". But it is not that simple. Relationships are built on mutual respect and trust.

Australia likes to point to its business ties with China-its biggest trading partner. But there is no guarantee those strong ties will last if the diplomatic relationship continues to deteriorate. New Zealand has a better relationship with China than Australia does. While it shares some of Canberra's concerns, it deals with them in a more diplomatic way.

A healthy and stable relationship between China and Australia will not only benefit both countries but assist regional and international stability and development. For example, both countries were signatories on Nov 4 to the 15-nation Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership between the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and Australia, China, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand.

Why Canberra persists in its campaign against China is open to speculation, since there are no historical issues or fundamental conflicts of interest between the two countries.

Morrison says that as a sovereign nation, Australia does not need to take sides between relations with China or with the US, adding that the bilateral relationship is by no means a transaction. But no one is asking Canberra to take sides-just to accord Beijing the same respect it gives Washington.

Australia seems to take for granted the prosperity of the country, which it widely acknowledges is due to China's spectacular growth over the past 40 years.

Chinese are still visiting Australia in increasing numbers, and Chinese students still prefer to study in Australia.

Australia seems to think the status quo will remain forever. But it won't. Nothing lasts forever.

The prime minister needs to think about the future and Australia's place in the region. He needs to make a point of visiting China on a regular basis. Other world leaders do so. It's not enough to head a conga line of business leaders once every couple of years.

He needs to rebuild the trust Canberra once enjoyed with China and call his people into line.

The author is a China Daily correspondent based in Sydney. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.