China is connecting hearts first, then roads

Facility connectivity has been a central focus of the Belt and Road Initiative, which was proposed by President Xi Jinping in 2013 and represents the largest development initiative of its kind in recent years.

The ultimate goals of the BRI-which comprises the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road-are to promote peaceful cooperation and common development around the world, where all countries can participate.

The initiative also aims to promote an efficient flow of materials and integration of markets to achieve diversified, balanced, mutually beneficial and sustainable development.

Implementation of the BRI in recent years has generated widespread interest and some concerns. On the one hand, developing and emerging economies have a huge demand for infrastructure development to stimulate economic growth. On the other, there are concerns about the environmental costs of infrastructure development, and about the financial burden that these infrastructure investments may add to the already challenging financial conditions in these countries.

These concerns are not new for people who have worked in international development. There has always been a struggle between economic development aspirations and sustainable environmental and social goals, which has to be sorted out by domestic debate and consultation. An interesting question is: What are the unique factors that have made the BRI attract so much attention?

In 2017 and 2018, our research task force selected four countries-Indonesia, Cambodia, Ethiopia and Kenya-as case studies to investigate infrastructure construction by Chinese State-owned companies.

The focus was on railway construction: the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed rail in Indonesia, the Addis Ababa-Djibouti electrified railway in Ethiopia, the Mombasa-Nairobi standard gauge railway in Kenya and the proposed railway project in Cambodia. The different types of railways represent both completed and uncompleted infrastructure projects within the BRI framework.

In 2015, the government of Indonesia accepted a Chinese bid over a Japanese bid for a 150-kilometer high-speed rail connecting Jakarta and Bandung. The rail is Indonesia's and Southeast Asia's first high-speed rail project. However, the project has been plagued by problems since its inception, including lack of proper environmental impact studies and consistency with spatial plans in Indonesia.

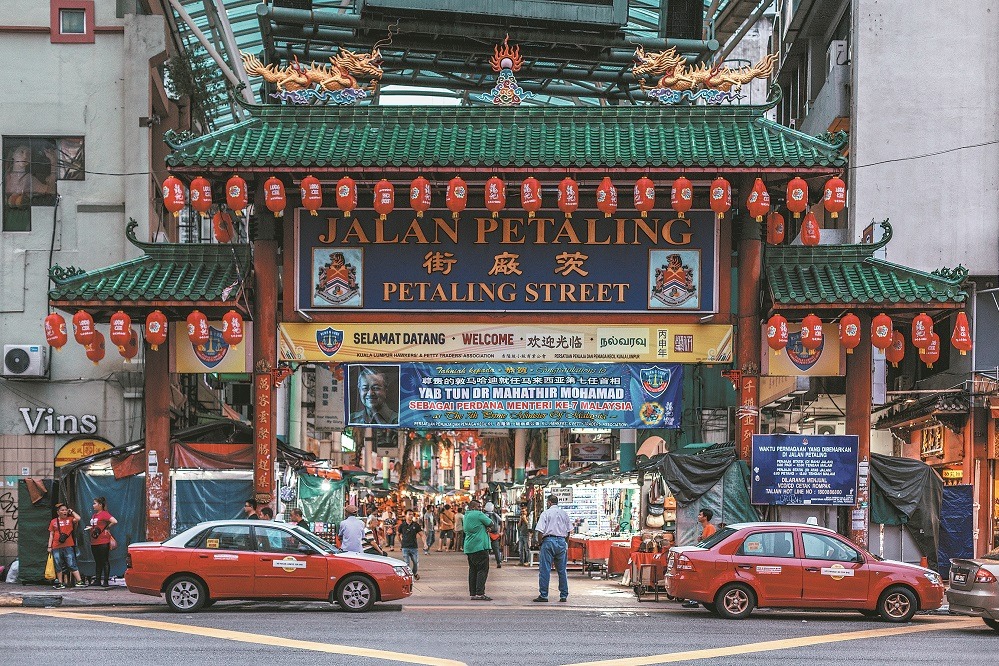

Another case is Cambodia, whose infrastructure is among the least developed in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations region. In 2016, China and Cambodia issued a joint statement, proposing to accelerate development of the new Silk Road and invest in the construction of transportation, energy, agriculture and water management infrastructure in Cambodia.

In 2011, the Export-Import Bank of China and China Civil Engineering and Construction Corp signed a $4 billion contract for the construction of the Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway, and the project was inaugurated in 2016. The link is the first multinational electrified railway built and operated by China in Africa.

In 2014, China and Kenya signed an agreement in Nairobi agreeing to fund the construction of the Mombasa-Nairobi railway. A financial agreement was reached with a total investment of $3.8 billion, 90 percent of which was provided by China Exim Bank and 10 percent by Kenyan financial funds. The railway began commercial operation in 2018.

We argue that the BRI can serve as a platform for China to transfer its successful development practices, which have been tested in China's own development experience since the early 1980s. After transforming China with high-speed rail lines, roads and electricity grids, Chinese companies are ready to export their expertise.

While the short-term focus of the BRI is mainly on infrastructure construction, the long-term implications could extend to other sectors. The whole idea of the BRI is not only about building a transportation route between China and the participating countries, but also a trade and investment corridor that can generate the goods and services to be transported along the routes.

In view of lessons learned from our case studies, a successful BRI project largely depends on people's trust and support in recipient countries. A BRI project can be accepted and recognized not only when the recipient country can benefit from BRI projects, but also when the major stakeholders in the country are able to perceive the benefits and gain them. There is a need to connect hearts between people in China and these countries before connecting roads in them.

Xue Lan is dean of Schwarzman College of Tsinghua University and professor at the university's School of Public Policy and Management. Weng Lingfei is a senior research fellow at the School of Public Affairs at Chongqing University. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

This commentary is based on a research that was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (No. 17CGJ007) and received assistance from Jeffrey Sayer, Rebecca Riggs, James Langston, Jun Zheng, Hari Sutanto, Lim Chhunleang and Dilamo Otore.