Noise and dust lead to Triassic treat

A young fossil restorer at a Shanxi museum spent three years helping to identify an extinct species.

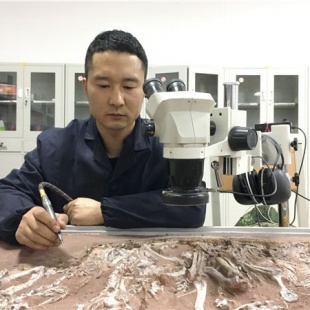

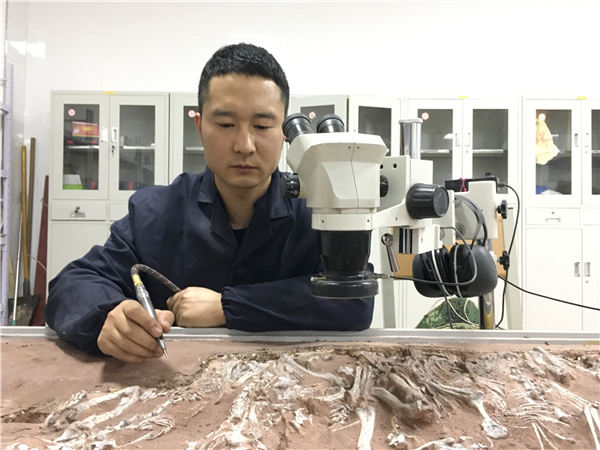

A man is working in a basement without windows amid a lot of noise and white dust on his table.

Lyu Bo, 32, is a restorer of animal fossils at the Shanxi Museum of Geology in North China's Shanxi province.

According to him, Wangisuchus tzeyi lived in the middle Triassic period (around 240 million years ago), and is thought to be older than crocodiles or even dinosaurs. The extinct animal from the archosauriformes reptile group was named by Chinese paleontologist Yang Zhongjian as Wangisuchus tzeyi in 1964, on the basis of fossilized fragments of jaw bones.

The genus is named after late Chinese archaeologist Wang Zeyi, who first discovered the fossil in the 1950s.

Some experts even doubted the existence of such an animal due to the lack of identification material.

But at a news conference held by the museum in Taiyuan, the provincial capital of Shanxi, last year, the research results of paleontological studies were announced, and the fossils of Wangisuchus tzeyi were shown for the first time. Lyu has been involved in the restoration of these same fossils for the past three years.

"More research into the newly restored fossils will help us identify the morphological characteristics of this animal and its categorization," Lyu says.

"They are the clearest and the most complete Wangisuchus tzeyi fossils we have yet found."

The Shanxi Museum of Geology had collected fossils in the province's Yushe county in 2010, including one of an unidentified headless animal, and another containing 11 other similar animals that were fully intact. Lyu began to restore the fossils in 2015, and after three years the museum worked with the Canadian Museum of Nature to identify the fossils as those of Wangisuchus tzeyi.

"The fossils were found among giant rocks, and required close observation to know which layer the fossils were in," says Lyu.

"In my work, any carelessness can lead to the destruction of the fossils. So I was extremely attentive," he adds.

After he had cleaned out some 30 centimeters of extra rock, he was very close to the fossils. He then used a hard needle to continue his work under the microscope.

"Sometimes I could only repair 1 square centimeter of the fossils in an entire day," he says, adding that on some days he felt dizzy, or his waist and back began to hurt after long hours of work.