Most people worldwide agree that fake news is a growing problem

Imagine if we could mine sales data to predict the outcome of major global events such as a US presidential election or even the soccer World Cup.

Sounds too good to be true? Well, that's because it is. But plenty of people, it seems, insist on believing it.

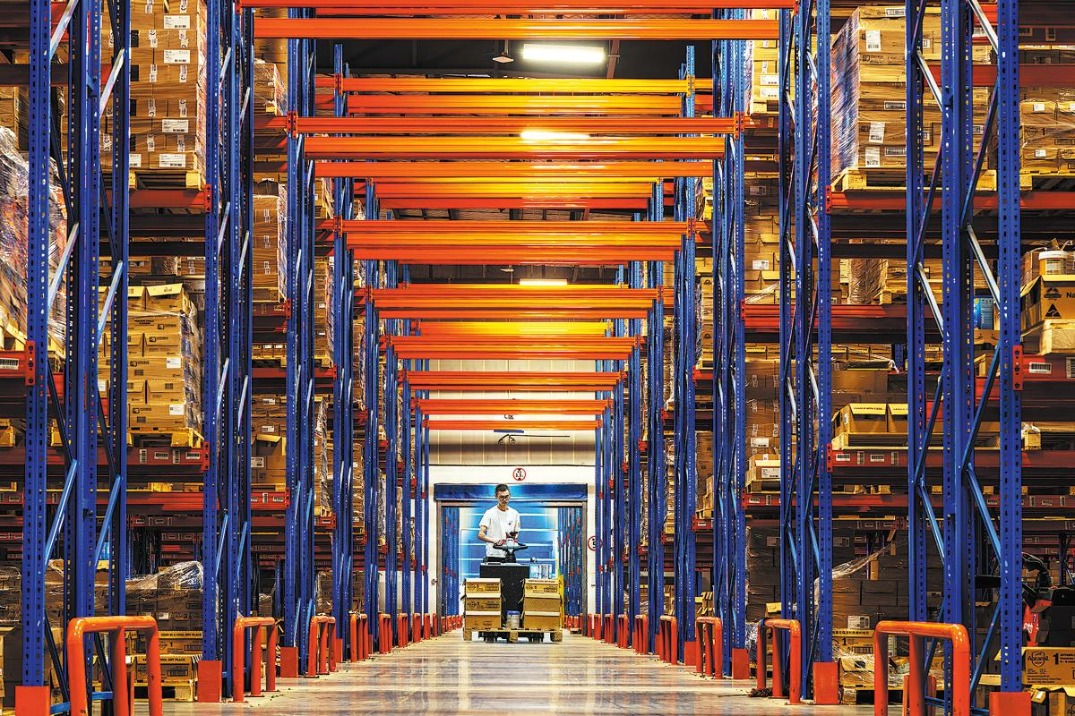

An internet meme that began in China has for some years promoted the predictive power of foreign sales figures from Yiwu in Zhejiang province, the world's biggest small commodities trading hub.

The "Yiwu index" phenomenon surfaced in 2016, when online postings claimed that a large volume of shipments of Donald Trump flags, hats and T-shirts from the Chinese city predicted his victory in that year's election.

Skeptics pointed out that more Americans actually voted for Hillary Clinton, even if they maybe bought fewer of her T-shirts. But that did little to dent enthusiasm for the index's alleged fortune-telling abilities.

Some online enthusiasts even suggested that Yiwu sales figures predicted the outcome of last year's World Cup.

The latest flurry came at the end of 2018, when rumours sweeping online chat sites suggested Yiwu's suppliers were running out of fluorescent safety jackets because of a surge in demand from Europe. Manufacturers were allegedly working overtime to meet orders.

That sparked predictions that France's "yellow vest" protests against higher fuel taxes and rising living costs were about to spread to countries such as Sweden and Switzerland.

At that point, the fact-checkers got to work. Media outlets, including China's Global Times, took the trouble to visit Yiwu and discovered that there were plenty of yellow vests on sale for anyone who cared to buy one.

Some suppliers said they had received no orders or enquiries from European customers and one seller said demand was actually down on the previous year, when Russian buyers stocked up on yellow vests ahead of the 2018 Winter Olympics.

It has yet to be seen whether old-fashioned facts will dent the faith of online enthusiasts who believe Yiwu sales have become a basis for predicting global trends and have the ability to turn everyone into an expert analyst of global affairs.

On past experience, the debunking of the "yellow vest" myth is unlikely to deter web chat appeals for a Yiwu index specifically geared to predicting the global future. The official Yiwu Index, established in 2006, fulfills the much more mundane task of reflecting the trading conditions for Chinese consumer goods.

As this column has noted in the past, a large segment of the online community is apparently prepared to believe virtually any crazy theory that is posted online and to dismiss fact-based reporting by the frequently derided mainstream media as "fake news".

Just like the internet itself, it is a global phenomenon. Surveys carried out by the international market research organization Ipsos have shown that more than half the world's population admits to having fallen for fake news, with Brazilians apparently the most gullible at 67 percent.

Most people around the world also think that their fellow citizens live in an information bubble in which they only share "facts" with like-minded people. Far fewer people are prepared to admit, however, that they themselves live in an information bubble.

In other words, while most people agree that "fake news" is a growing problem, they also believe that other people are more likely to be victims of it than they are. At the top end of the scale, 77 percent of Americans believe other people live in an information bubble, according to Ipsos research.

Perhaps it is a natural human tendency to believe that we are more rational and well-informed than our neighbours. The reality, however, is that many people make vastly exaggerated estimates when questioned about hot-button issues such as crime or immigration.

And many people who would instinctively scoff at anyone who believed in alien UFOs will no doubt happily continue to accept the predictive power of Yiwu's yellow vest sales.

There is no short cut to establishing a more fact-based culture online. The preference of humans for believing whatever they like, regardless of the reality, long predates the internet.

Last year, we looked at the new Piyao platform, established by the Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission and Xinhua News Agency, to incorporate the work of scores of fact-checking websites.

In 2019, it might be worth going a step further and encourage schools to introduce skepticism training. Lesson one could be: don't automatically believe the latest item that just popped up on Twitter or Wechat. It is never too early to start helping the young to distinguish fact from fiction.

For, as well as being an potential source of false information, the internet is also a huge resource for fact-checking if people know where to look. There is plenty of independent, accurate information available, even if it is sometimes less dramatic and entertaining than the fake stuff.

A good rule of thumb - old-fashioned journalists use it all the time - is that if something sounds untrue, it probably is. So, always check before you hit the "send" button.

Harvey Morris is a senior media consultant for China Daily UK. Contact the writer at harvey.morris@gmail.com