Film explores Unit 731 and its dark wartime past

From a village in Central China to a US military base, to a controversial Japanese shrine, a documentary film attempts to piece together a more complete picture of the Japanese Army's Unit 731 and how its war criminals walked free.

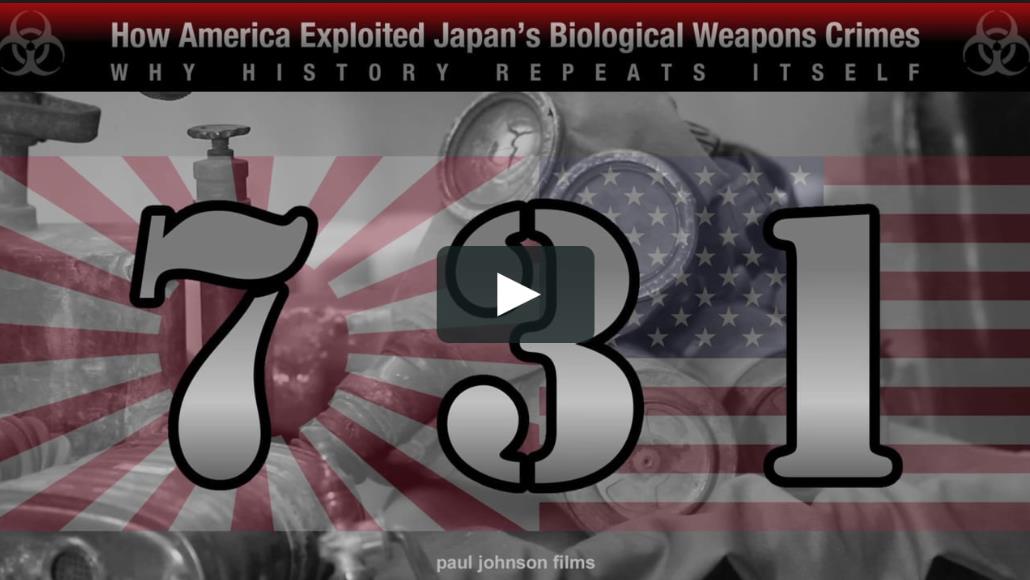

The 52-minute film, 731-How America Exploited Japan's Biological Weapons Crimes, contains interviews with remorseful Japanese soldiers, Chinese survivors, and activists and scholars to recount some of the cruelest atrocities committed in the 20th century.

"There's almost no knowledge of Unit 731 in the West. This is a sad chapter in recent human history," said Paul Johnson, the director. He worked for three years on the film, which is now streaming on Amazon and Vimeo.

"I believe the old saying: If we are going to not repeat the terrible mistakes that we made, we need to start by knowing about them," he said.

The notorious Unit 731 was set up by the Japanese Imperial Army in 1933 in Northeast China to develop diseases for use as weapons, including plague, glanders, anthrax and typhus. The Japanese partly destroyed the headquarters in Harbin when they were defeated in 1945.

According to the film, bombs laced with plagues and anthrax were exploded near Chinese prisoners who were tied to stakes; other experiments include forcing prisoners to drink cholera-contaminated milk or injecting deadly diseases directly into their bodies. Even small children were taken and fed with chocolate filled with anthrax.

One of the most common experiments at Unit 731 was dissecting diseased bodies alive without anesthetics. The subjects, called marutas, or logs, were mostly Chinese and some Russians, and even Allied prisoners of war.

Every year, 400 to 600 new prisoners were taken to Unit 731. At least 5,000 people died from the tortures they underwent there during the 13 years, according to the Unit 731 museum, which was built on the relics.

The pain from the Japanese attack lives on in the bodies and memories of the survivors. In Central China's Changshan, some older people still remember they were exposed to something sprayed in the open fields when they were children; the infection left, but the wounds never heal.

Half a million Chinese people are estimated to have been killed by this method of biological warfare, according to data gathered by Pacific Atrocities Education, which recently organized a screening of the film in San Francisco.

"The test performed on innocent civilians is a dark chapter in world history. Experimentation on people was just horrible," said Brian Peters, a San Francisco resident.

"They (the Japanese Army) kept using it on defenseless civilians who couldn't fight back. That's fundamentally dishonorable, and it's kind of strange, as the Japanese are always about honor," he said.

What impressed Peters the most in the film is the scene of an old Japanese soldier, who worked at the unit, recognizing the crimes on his deathbed.

"He still has his ceremonial sword and he is trying to make tiny bit of amends by giving his sword back to the museum (the Unit 731 museum in China)," he said.

"Some individual Japanese have broken out of their government and societal consensus to try to suppress this, but it's so late now. Almost everyone is gone, the victims and the perpetrators," he said.

In exchange for the Japanese findings about the effects of biological weapons, the US not only gave immunity to the leaders of Unit 731 but put them on the American payroll, according to the documentary.

"Most of the data is still classified, but we know where the Japanese findings about the effects of biological weapons went — to Fort Detrick in Maryland, which continues to be the headquarters for American biological weapons work," said Johnson.

The film shows that Edwin Hill, a Fort Detrick science chief, wrote in a 1947 report that "such information (Unit 731 data) could not be obtained in our own laboratories because of scruples attached to human experimentation".

"The world is changing, the relationship with China is more important than ever. And we need to get it right," Johnson said. "Part of getting it right means we need to understand what happened in their history."

Contact the writer at liazhu@chinadailyusa.com