China Reform and Opening – Forty Years in Perspective

ARRIVING IN BEIJING – 1981 Re-visited

Editor’s note: Laurence Brahm, first came to China as a fresh university exchange student from the US in 1981 and he has spent much of the past three and a half decades living and working in the country. He has been a lawyer, a writer, and now he is Founding Director of Himalayan Consensus and a Senior International Fellow at the Center for China and Globalization.

He has captured his own story and the nation’s journey in China Reform and Opening – Forty Years in Perspective. China Daily is going to run a series of articles every Thursday starting from May 24 that reveal the changes that have taken place in the country in the past four decades. Keep track of the story by following us.

Laurence Brahm in the Forbidden City, Beijing. Photo taken in the 1980s. [Photo provided to chinadaily.com.cn]

It was late spring when I first arrived in Beijing in 1981. The airport felt like an oven, it was baking in a stifling flat heat. I was sweating. There was no conveyer belt for luggage. Scowling airport staff just threw luggage off a cart. They could not care less what was inside your bag. There was no concept of service.

I remember walking out of the cavernous Soviet era airport with art deco red stars on the ceiling, right into Beijing’s broiling summer heat. I later learned there was no spring season in this city. Everyone in the crowd waiting outside wore either green army or blue worker pants. Men and women alike wore a short sleeve shirt that was so poor in quality you could see through it. I tried speaking some broken Mandarin to find my way. Nobody answered. They simply stared at me.

I felt like an alien who had dropped out of space. It was like a science fiction movie, Planet of the Apes, or something like that.

The old narrow road from Capital Airport into Beijing seemed long. There were poplar trees lining both sides. The bus broke down several times. Each time, everybody got out talking all at once and tried to fix it. I thought, China’s economy was like that bus!

My first stop like most foreigners in those days was the Friendship Store, a five story cavernous department store reserved for foreigners. It was then the tallest building on Chang An Avenue. I bought a Coke. It was imported and cost one dollar. That would have been more than any Chinese could have ever conceived of spending on a drink. At that time, there was only one local soft drink called qishui’er meaning “gas water.” It tasted like it sounded. It came in green and orange colors, with a spectrum of shades like a teenage punk rocker might dye their hair.

Laurence Brahm. Photo taken in 1981. [Photo provided to chinadaily.com.cn]

My Chinese teachers were distraught that I paid one Dollar for a Coke thinking I was totally decadent, and told me so to my face. In those days, ordinary Chinese citizens were not permitted to enter the Friendship Store. And of course, nobody could afford an imported Coke.

On that stiflingly hot day that simple act of buying a Coke brought into sharp focus the distortions and disconnected perceptions between the developed and underdeveloped world. That one-Dollar Coke juxtaposed all of the economic assumptions I had been brought up with.

Most Chinese did not have access to money because in 1981 China hardly had any money in circulation. And even if someone had money, there were few commodities to buy. Aside from the Friendship Store, most state-run department stores had empty shelves, or just blue and green pants.

It was an economy of scarcity.

I was a fresh university exchange student, and very idealistic. The idea of improving China’s economic condition started as a vision and quickly became an obsession. It was the main thing that motivated me each day as I filled up a cheap white tin cup with sticky venomous Shanghai produced instant coffee. Soon I learned to drink tea. Slinging a green army bag over my shoulder I went to Mandarin class each day. Determined to learn this language, I was convinced it would be the key to opening up the Pandora’s box that was this nation’s predicament.

China’s economic backwardness struck me. Coming from America, then the most affluent society in the world, I had to get my mind around China’s lack of everything. Was it possible to change this condition? I asked myself as I walked along the lake at Nankai University each afternoon. Chinese students gave me their well-used red-jacketed little books as gifts. At first, I thought they wanted to share with me thoughts in the books. Realizing their nostalgia value, I began to collect these old books. Then they started to sell me more books.

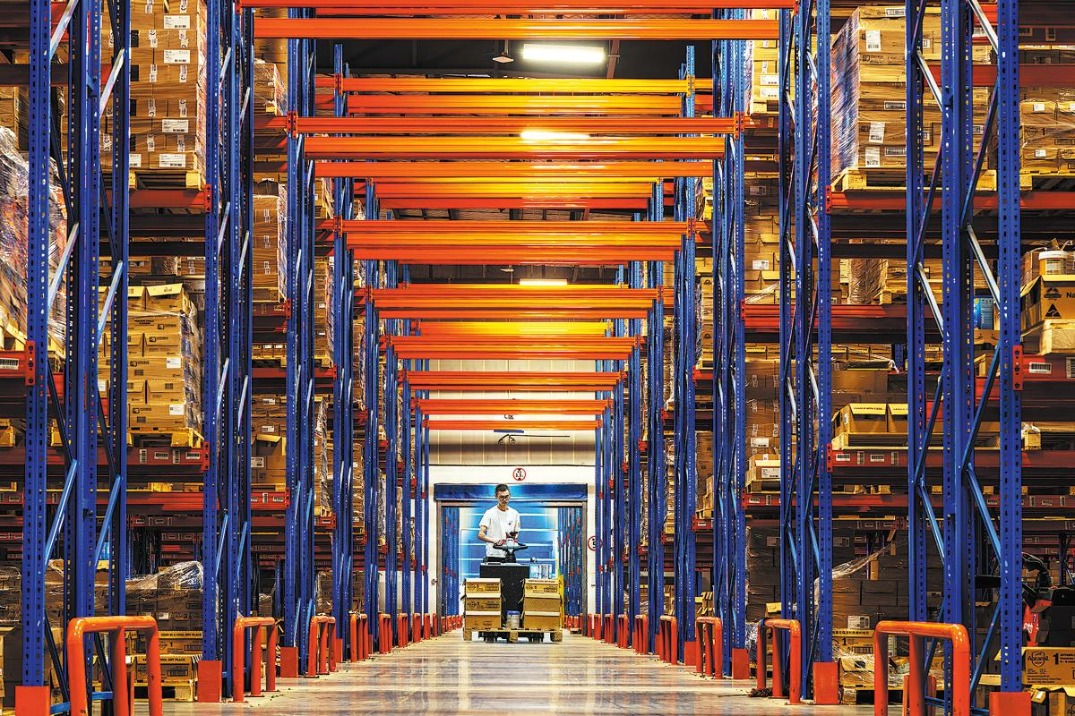

Within two decades China would shift from a position of complete scarcity to one of over-supply of virtually every product and service. Three decades later it would become the second largest economy in the world, the most powerful economic force to be reckoned with next to the United States.

To me it was unimaginable that this would happen so quickly or that I would play a part in this process. The thought was furthest from my mind on that dry hot day, as I drank my Coke in the Friendship Store, its dreary staff behind dusty counters stacked with grotesque jade carvings and box-like imported television sets lazily staring at me….