Japan's aging population a timely lesson for China

People in Japan tend to live longer, and stay healthier in their later years, with an increasing number of pension-aged people living alone. Japan's National Institute of Population and Social Security Research has projected that households headed by people aged 65 years or above will account for 44.2 percent of the total households in 2040, up from 36.0 percent in 2015.

Japan is on a fast track to "ultra-age" with people aged 65 or above accounting for 28 percent of its total population; it was 26.7 percent in 2015. The number of births in 2017, as Japan's Health Ministry said, fell to its lowest (about 941,000) since records began in 1899.

Demand for care services for elderly people has boomed. A shrinking working population means fewer able-bodied adults are available to look after the elderly. There is a shortage of state-provided facilities for the elderly, and private healthcare is expensive. Many elderly people do not have the heart to burden other family members who may not live nearby or may be struggling themselves. They choose to live alone, and often die alone. Sometimes, days, if not weeks, go by before someone discovers their remains.

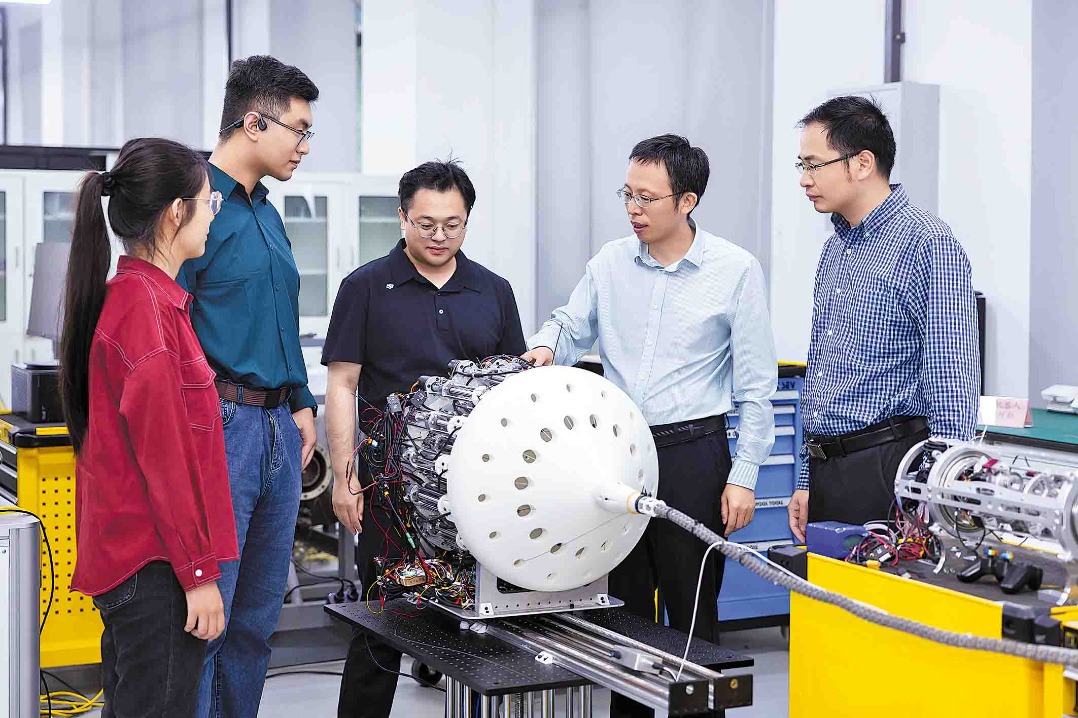

The Japanese government says the country will be short of 380,000 health nurses by 2025. Since Japan is reluctant to welcome immigrants, the government has turned to advanced robotics, which it has invested heavily in, to meet the shortage. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe believes robotics "could help the country overcome the handicap of a fast-aging populace and a declining workforce and to help the country to use robotics, from large-scale factories to every corner" of Japanese economy and society.

Government subsidies hog some two-thirds of the research and design costs for the development of various healthcare robots. About 5,000 nursing homes across Japan are testing robots, funded partly by government.

From robotic walkers to robot companions, Japanese companies aim to create cost-effective robots that will assist the elderly with a range of physical issues, even emotional and psychological issues.

A study found that using robots encouraged more than one-third of the people to become more active and "independent". At a time of increasing elderly populations and dwindling public resources, technology is helping us to embrace a future where some of societies' most vulnerable people will be put under the care of machines. It is no longer a scenario found only in science fiction. Yet there is no robot that can provide emotional support to the elderly, by listening to their needs, taking care of them and, in general, making their twilight years happy.

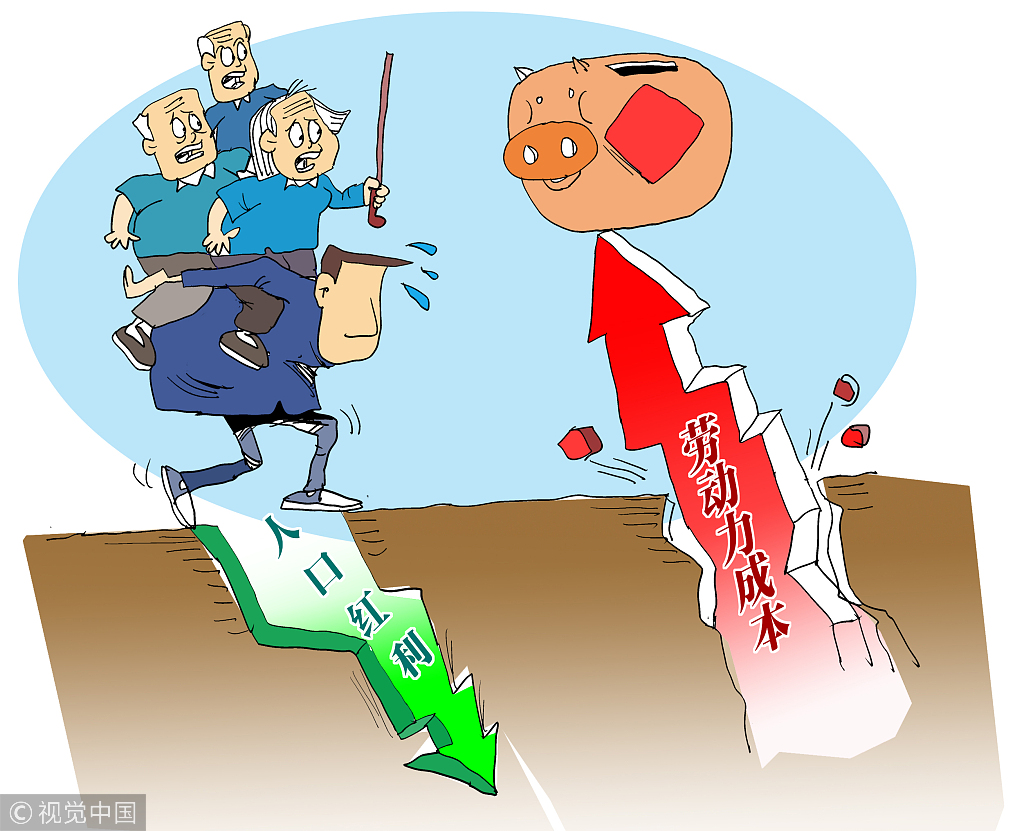

The making of Japan's demographic time bomb over the past more than two decades provides a case study for China, which too is faced with a fast aging population. About 17.23 million babies were born in China last year, about 630,000 fewer than in 2016, according to the National Health and Family Planning Commission. People aged above 60 accounted for 17.3 percent of China's population in 2017, compared with 16.7 percent in 2016. Not surprisingly, therefore, many Chinese experts expect the country's gray population to hit the 400 million mark by the end of 2035.

With insufficient elderly care facilities and unbalanced supply, China may find it tough to cope with the rapidly increasing number of senior citizens. It is highly unlikely that China's population will shrink in the near term like that of Japan. However, since the birth rate in China is expected to remain below the replacement rate of 2.1, it appears China, like Japan, will see the average age of its population rising steadily in the foreseeable future.

To meet the demographic challenges, the authorities have to make policy changes, which Japan is unwilling or unable to do, even consider. But China should heed the serious signals its aging population is sending, and take appropriate and timely actions.

The author is China Daily Tokyo bureau chief. caihong@chinadaily.com.cn