In search of the elusive snow leopard

Those who want to see one of China's rarest animals face a journey that can be terrifying in parts

I finally woke up when my head bumped against the window of the car as it jolted down the rough mountain road. Behind us, the driver of the Toyota Land-Cruiser was hooting and shouting: "The rear tire! The rear tire!" Our driver brought the car to a slow halt on a flat section of the road.

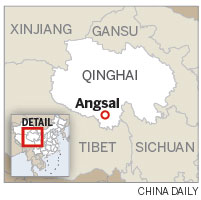

We were on the only path leading deep into the mountains of what is regarded as the home of snow leopards, Niandu Village, in Angsai town, a remote place in Qinghai province among the wild mountains and rivers of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Our destination, where we hoped to see wild animals such as white-lipped deer, was still about 80 kilometers away.

The driver and the other three passengers of the car jumped out to see what had happened. The right rear tire was punctured. On such occasions I am next to useless, and my phone was picking up no signal, so I decided to take a short stroll in my thick down jacket and ski pants while the flat tire was being replaced.

| Zhaqu River, in the upper reaches of the Lancang River in Niandu village, Angsai town, in the Yushu Tibetan autonomous prefecture in Qinghai province. Yang Yang / China Daily |

| Drivers fix the punctured tire of the Land Cruiser. Yang Yang / China Daily |

We were on the fifth day of a 10-day trip to the Three-River-Source National Park, the first of its kind in China. Approved by the government in 2015, China's national park system aims first and foremost to preserve regions with ecosystems and natural heritage unique to China. Under the national park system, mountains, rivers, woods, fields and lakes are managed by a single department instead of five different departments. The national park, in addition to being charged with preservation, will be open to scientific research, education and moderately developed tourism.

The Three-River-Source National Park, as the name indicates, contains the sources of three big rivers, the Yangtze River, the longest river in China, the Yellow River, the second longest river in China, and the Lancang River that runs into Vietnam, the Mekong River.

The park, covering 123,100 square kilometers, about the size of Greece, is home to not only mountains, rivers and unique plants and wild animals, but also aboriginal people. More than 60,000 people in 16,000 households in 53 villages that belong to 12 towns live mainly on the husbandry. There are 2,400 households that live in poverty.

As a result, preserving the natural environment is just a part of the work of national park authorities. How to improve the lives of those within the park and have them join in the preservation of the national environment is also important for the system so humans can live harmoniously with wild animals.

Niandu Village, near where we had our puncture, is one of the 53 villages in the national park.

We were at about 4,000 meters above sea level. Although I could not move fast, I felt much better than two days earlier, when we ascended from Xining, at 2,300m to the Yellow River-Source region of Maduo county 4,300m where I had spent a sleepless night, suffering from a bad headache caused by oxygen deprivation.

We were now in an open valley. The Zhaqu River, an important upper branch of the Lancang, wound through the mountains afar. There were few trees other than cypresses in sight. Grass carpets that had turned yellow in late September extended onto the low mild slopes of the mountains. It was a splendid view.

Before long, chunks of dark cloud pressed down above us and it started to rain. A gust of wind blew, the air become more chilly and it rained more heavily. Luckily we got to the car in time. As we jumped into it, and before I could roll down the window thunder boomed and hailstones blasted the car, hitting the roof like bullets.

For me, this sudden change of weather was exhilarating. The hail soon stopped but the rain continued. A mountain road that at first had been merely difficult soon became dangerously muddy. The Land Cruiser drivers cautiously eased their vehicles down the continuous 60-degree grade roads punctuated by hairpin bends.

Sometimes the road was so narrow that the cars barely missed scraping the mountainside. At other times it was as if we were floating high in the air above the swiftly flowing yellow water of the Zhaqu River. Stones and rocks that tumbled down the mountains scattered over the road. The view was amazing, but I was so terrified that several times at the local holy mountain on whose top sat a naturally formed Buddha statue I prayed that we would not die, either by plunging over a cliff, or being crushed by falling boulders.

In fact we had entered the mountains the day before, but we arrived too late. Halfway in we came across the remains of a half-eaten domestic yak beside the road, which one of our party reckoned had fallen prey to a snow leopard. Some members of the team had gone deeper into the mountains and told of seeing white-lipped deer and foxes, so we were here again to try our luck.

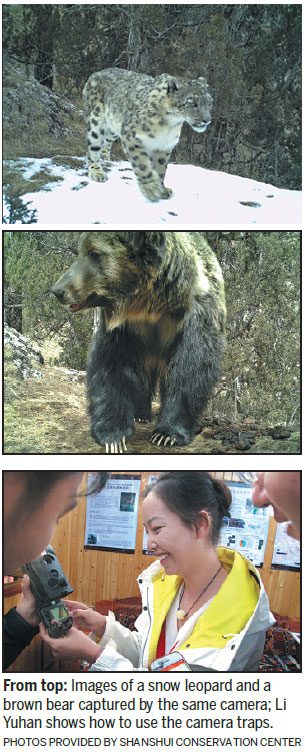

Angsai town, with its well-preserved natural environment, is home to many wild animals, such as leopards, brown bears, white-lipped deer, blue sheep, argali, white-eared pheasants and the most famous of them all, the snow leopard.

But before Angsai was designated a pilot town in China's national park system in June last year,

nobody knew how many kinds of wild animals, especially big carnivores, lived in the area.

By late September 42 herders had been trained to place 50 camera traps in 1,250 sq km of wilderness and retrieve them every three months. At the end of this year more than 50 camera traps will have been deployed in another 1,250 sq km to capture animal images for research purposes or publicity.

"The cameras will activate when they sense the temperature of an approaching animal," said Li Yuhan, 23, an undergraduate of Peking University, who was in charge of the orange station of an NGO, Shanshui Conservation Center.

"Our station consists of a makeshift building made of containers that can be dismantled and moved away any time."

She showed us around the building not far from the Zhaqu River, which could house up to 12 people. There was solar power for basic electricity needs, but it was out of signal range for phones.

"We regularly train the locals how to install a camera so it can't be moved by wind or animals," she said, adding that "they know the places those animals frequent".

Since the station opened in July it has housed 10 PhD candidates researching topics such as snow leopards, stray dogs and the holy mountains.

"We expected more researchers and volunteers to join us," she said.

Last year a camera trap captured the images of seven different animals: a leopard, a brown bear, a white-lipped deer, a lynx, a red fox, a snow leopard, and a white-eared pheasant. Other cameras captured the images of wolves, otters, blue sheep and argali.

"This was a principal result of our monitoring last year," said the head of Angsai town, pointing to framed photos on the wall of his office.

"Over the past dozen years these photos have proven the existence of leopards in Three-River-Source regions for the first time, and they share habitats with snow leopards. They also show that the Lancang River-Source region is one of the areas in China rich in top carnivores whose habitats overlap."

Thus far they had found traces of 24 snow leopards and seven leopards in the area. They had also captured the images of two mating snow leopards.

However, as the natural environment has improved, the number of wild animals increased, and they are often fall victim to predators.

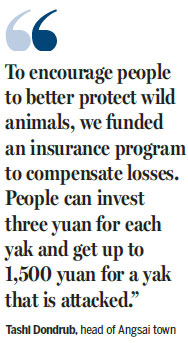

In 2015, predatory attacks caused the 1,930 households in Angsai town to lose 4.6 yaks each on average, the biggest loss for a household being 28 yaks, the local government says.

"It was a big loss," Tashi Dondrub said. "To encourage people to better protect wild animals, we funded an insurance program to compensate losses. People can invest three yuan for each yak and get up to 1,500 yuan for a yak that is attacked," said Tashi Dondrub.

From January to August those who suffered as a result of 154 yak attacks received compensation. In addition to compensation, locals benefit from the operation of national park in other ways.

Halfway to Shanshui station the previous day, we came cross a herdsman, Dongsheng, 28. In camouflage uniform, wearing a red hat and a red armband, he sang a song in Tibetan that eulogized his beautiful homeland.

Coming from a poor five-people family, on motorcycle or in his car he patrols four mountains, looking out for the theft of plants, wild animals, picking up garbage and reporting on yak attacks. In fact the job entails looking after the ecosystem of the mountains in his charge.

Dongsheng, one of the 468 patrollers in Angsai town, all from poor families, is paid 1,800 yuan a month from national park funding. Patrollers on similar duty in the Yellow river-and the Yangtze River-Source regions are paid similarly.

Saying goodbye to Dongsheng, we continued to drive and pulled up beside a white tent, besides which were more than 60 black and white yaks, grazing quietly at dusk. They were with a nomadic family of four that would migrate to different grasslands in different seasons. The daughter and mother were at home.

The father, Yonta, is a patroller, and one of the 42 herdsmen who placed camera traps to record animal activities. The family is one of 15 official reception families in the town for people who want to experience life here and to observe animals and plants in the region.

"The services start from the airport," said the patroller's wife, Namsai Voimo, 46. "We pick up customers from there and take them to the places that wild animals frequent. We charge 1,500 yuan a day for a car and guide service, and 200 yuan each for board and lodging a day.

"In April we had four British people here who wanted to take photos of snow leopards, but one got severe altitude sickness, so they stayed for only two days and left."

When we finally reached our destination, the new tire suffered the same fate as the first one, and we spent some time waiting for another spare to be delivered from the town, 100 kilometers away. The only animals we saw were marmots and stray dogs.

I climbed up a hill slowly to find a fabulous view: on the right, yellow swift current carrying soil washed down by rainfall ran through the grand mountains. On the left, the naturally formed Buddha statue at the top of the holy mountain sat in a clear blue sky facing another mountain shrouded by thick dark cloud. Before long, sunshine shone through so that one side of the mountain appeared bright and warm, and the other dark and cold.

Because of the altitude and the cold I got hungry very easily, so I went down the hill to eat a bowl of Tibetan noodles in a warm, white tent. Besides it were two rows of smaller tents in many different colors. The owner, a middle-aged mother of a 8-year-old girl, said it was the end of the tourist season here. In July and August the place was crowded with jolly visitors from outside, she said. The girl shyly handed me two candies. The musician Sonam Dargye played a Tibetan song on Mandolin for us.

Outside, it was nightfall and our return journey in the darkness on a dangerous road would take many hours, during which we might well pass hunting leopards hiding beside the road. Before I rushed back to the car, the owner said: "Come next year, we will take you to a wonderful place to see the animals."

Yet locals, who venerate nature, are not exactly keen on a tourist influx even if it benefits them financially, because they believe it will disturb the lives of wild animals, Tashi Dondrub said.

"They oppose the idea, saying the animals they used to see along the roads will not show up anymore."

Under development plans, 2 percent of the Three-River-Source National Park would be preserved for wildlife, and these areas would be off limits to the public.

yangyang@chinadaily.com.cn

| Some 60 yaks owned by Namsai Voimo and Yonta, a nomadic family in Niandu. They migrate to other grasslands in different seasons. Yang Yang / China Daily |

| A venerated mountain provides the backdrop for these horses. |

| Dongsheng, a patroller of four mountains in Niandu, is responsible for monitoring ecosystem. |

| Namsai Voimo in front of her white tent where she receives tourists who want to experience the local life and observe wild animals. |

(China Daily 10/28/2017 page13)