Labor rights make a world of difference

Brazil ranks second in the world for its number of lawyers per capita, only the United States has more. Now I know why.

The many Chinese and Brazilian business executives I met during my recent trip to Brazil continually complained about the strict labor laws that often make them defendants in court.

"Even sending an e-mail to employees after work hours is illegal," said one newly arrived Chinese businessman, with a puzzled look on his face.

While this may sound bizarre in China, where employers and employees often send and check e-mails after work, Brazil has a new law that requires companies to pay overtime to employees who make or receive work-related e-mails or phone calls out of office hours.

Employers can be sued if employees are required to do things not included in their job description, and they need to select their words very carefully when talking to employees or they may be accused of discrimination. And, according to the business chiefs I met, even if they do treat their workers well there will be a strike at the end of the year to demand a pay raise.

Brazil's labor laws, which are embedded in the country's Constitution as non-negotiated rights, are probably among the strictest in the world.

What are mandated as legal rights for Brazilian workers, such as a mandatory "13th-month" bonus, 30-days leave, a workday that cannot exceed eight hours, or a workweek that cannot go beyond 44 hours, are often considered perks in other countries.

Because of the huge mandatory benefits and contributions and taxes paid for employees, employers often find that the cost of hiring a worker is nearly double the base salary.

I am not surprised that Chinese business executives feel intimidated by Brazil's strict labor laws because many of these labor rights are either non-existent or at best optional in China.

Recent stories about Foxconn, an original equipment manufacturer for Apple in China, are quite telling. When Foxconn was forced to limit overtime for its employees in China, the migrant workers protested because they would lose money by not working overtime. To some, even 36 hours of overtime a month is far from enough.

I teased Sergio Amaral, the former Brazilian trade minister and now chairman of the China-Brazil Business Council, about how Brazil can compete with China when Chinese workers want to work 12 or more hours a day.

But I doubt workers in China would be so willing to work that many hours if they were paid enough in the first place.

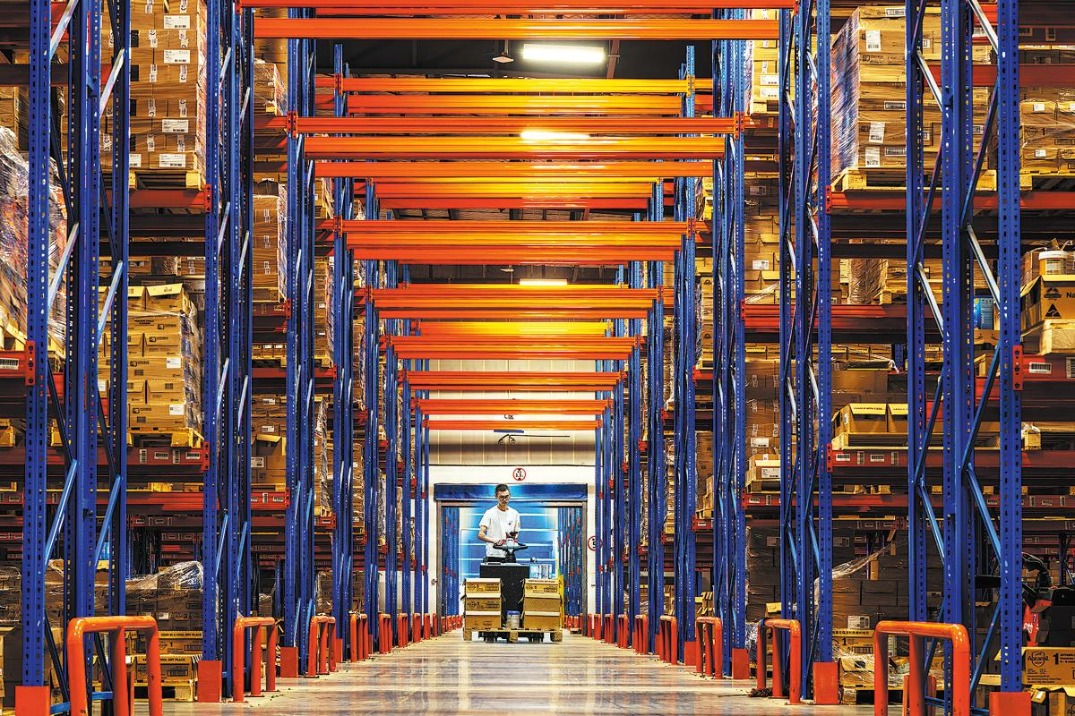

While Foxconn has become the focus for labor rights violations in China, the company was forced to offer workers at its plant in Brazil much more due to the country's strict labor laws. The wages are twice as high and workers get six times as many days holiday. At the same time, workers at the Foxconn factory in Brazil have bargained for decent wages, health plans, profit-sharing, food and transport and six months of paid maternity leave, in addition to the 44-hour maximum workweek set by the law.

In the World Bank's 2010 Doing Business Report, Brazil was ranked 138th out of 183 countries for the difficulty of employing workers. One of my friends, an editor at a major Brazilian newspaper, said that many employers in Brazil regard its labor protection as a problem.

While Brazil may want to change its tough labor laws in order to stay competitive, Chinese workers, both blue- and white-collars, definitely need some of the rights and protection offered to Brazilian workers.

I'm not sure if sending e-mails or text messages after work hours should be regarded as illegal or overtime, but over-exploitation of workers and taking advantages of lax labor law should be ended.

The author, based in New York, is Deputy Editor of China Daily USA. E-mail: chenweihua@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 07/06/2012 page8)