|

|

|

|

30th Anniversary Celebrations

Economic Development

New Rural Reform Efforts

Political System Reform

Changing Lifestyle

In Foreigners' Eyes

Commentary

Enterprise Stories

Newsmakers

Photo Gallery

Video and Audio

Wang Wenlan Gallery

Slideshow

Key Meetings

Key Reform Theories

Development Blueprint

Li Xing:

Teachers like Li need our support Alexis Hooi:

Going green in tough times Hong Liang:

Bold plan best option for economy Movers and shakers

By You Nuo (China Daily)

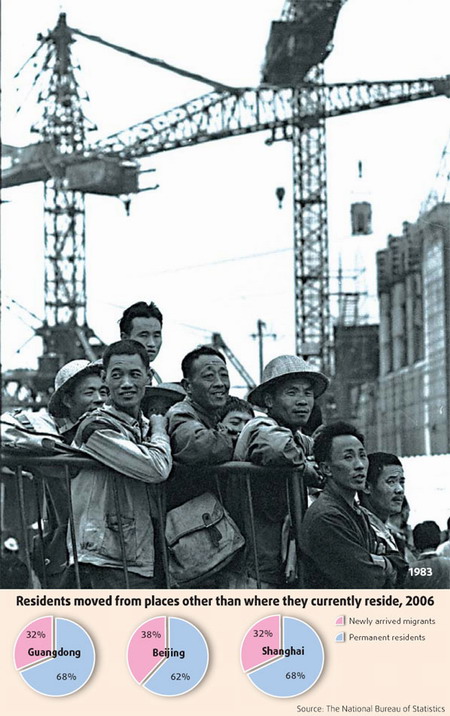

Updated: 2008-04-14 17:13  These people, don't be mistaken, are farmers. Although they work on many construction sites in China, and many of them have been working in industrial jobs for their entire lives, they are still called farmers - at least based on their identification cards. However, they are the largest group of industrial builders in modern China. They work on projects like the Gezhouba Dam, a hydropower station on the Yangtze, where our photographer caught them in 1983, and Beijing's Olympic facilities, shown in the color picture taken in the early weeks of 2008. They are called rural workers in Chinese (an obvious misnomer, for what they are best suited for are industrial jobs), and are known as migrant workers in English (which is not true in many cases as well, for some of them have been living in cities for more than a decade).

But whichever label you chose, it is indisputable that the workers are responsible for Chinese cities' ever-changing skylines. Beijing should extend them special thanks for building the city's Olympic venues, most famously the two buildings in the color picture's background - the National Stadium, nicknamed the Bird's Nest, and the National Aquatics Center, or the Water Cube. Looking back at the course of China's economic reform of the past 30 years, the migrant workers' role is much larger than the new cities they have built - and larger than the GDP (gross domestic product) they have contributed. The phenomenon also represents a breakthrough in the conventional formula of development, where rural development is pinned on agricultural modernization alone - higher farm yields, more cash crops, etc. But agricultural modernization is usually a costly endeavor, from introducing new farming techniques to building new villages. More often than not, that also leads to the government's protective prices, or other protectionist measures such as farm subsidies.

Instead, China has channeled much of its rural labor into more easily manageable urban and public infrastructural projects. The benefit of this development model is that it allows China, which has the world's largest group of rural people, to improve their income structure without acting so protectively in trade. In fact, export-oriented manufacturing, a sector with the largest sum of foreign investment in the developing world, has become a main source of new jobs for migrant workers, along with government-funded infrastructure projects like those featured in the pictures. The disadvantage of the Chinese model is that it has created a huge gap between regions where industry has absorbed most rural labor and regions where industry remains weak. One complication is that where infrastructure is weak, industry is usually in a lackluster state. So income discrepancy has grown into a social malady. However, the solution is not hard to define. China needs to build more public infrastructure to enable local people to diversify their commercial interests. One Chinese economist once joked to me: "It is like having (British economist John Maynard) Keynes as our chief development planner, and (former Austrian minister of finance, sociologist and economist, 1883-1950, Joseph) Shumpeter, as our commerce minister. If only China does it purposefully."

|